- 1 The history of Kojima Shōten: The flame undying for 220 years.

- 2 Rustic and tough: Lanterns that reflect the character of their makers.

- 3 Shun Kojima

- 4 Ryo Kojima

- 5 Parent and child, master and apprentice

- 6 How Kyoto lanterns are made

- 7 Lighting the city: Kojima Shōten’s lanterns around town

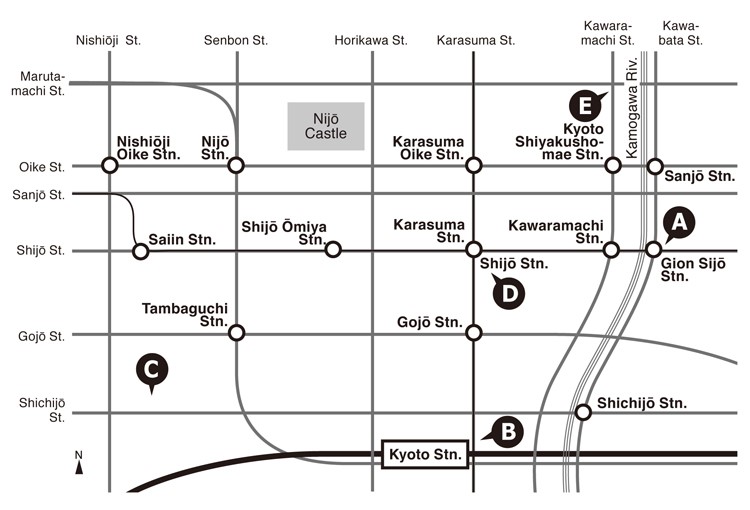

- 8 A. Minamiza (120cm x 185cm)

- 9 B. Kyōya

- 10 C. Compass

- 11 D. TaKaMaDo

- 12 E. Isshindo

- 13 Upholding tradition, linking to the future

- 14 Chibi-maru【Small ball】

- 15 Washi-mari【Balls made of washi paper】

The history of Kojima Shōten: The flame undying for 220 years.

The history of Kojima Shōten, the venerable Kyoto lantern makers, stretches back approximately 220 years, to around the year 1800. In fact, while the oldest documents on record of Kojima Shōten date back to this time, it is believed that the store actually opened its doors even earlier. Indeed, around the time when Kojima Shōten first opened for business in the late 18th century, Marie Antoinette was executed, Thomas Jefferson was elected as the third President of the United States, and the ukiyoe artists Sharaku was wowing Japan with his woodblock prints. With this perspective, we can appreciate the weight of the history the Kojima family members have inherited. The lanterns crafted by Kojima Shōten have long illuminated temples, shrines, and the estates of samurai and merchants. We spoke to the two young keepers of the flame, passed down to their generation in a manner not unlike an Olympic torch relay.

Rustic and tough: Lanterns that reflect the character of their makers.

What sets Kojima Shōten’s lanterns apart is the distinctive manufacturing method called jibari-shiki (“affixing style”). The manufacturing process and the materials used in this method are quite different to those usually used for other lanterns. Most other lantern craftspeople employ a method known as makibone-shiki(“wound bone style”), in which the frame is made by winding one long, thin bamboo strip (bone) into a spiral frame. This produces a neat frame relatively easily, and is commonly used in this modern age to satisfy the need for an efficient rate of production.

In contrast to makibone-shiki, in Kojima Shōten’s traditional jibari-shiki method, both the bamboo used for the frame and the paper attached to the frame are relatively thick. The frame is made by fashioning single strips of bamboo into individual rings, and then fixing these in place with string. This means that a tremendous amount of time and effort goes into completing each lantern. The result is a somewhat rustic and tough lantern. Not only is the lantern robust in terms of function, the bold texture of the wood and the paper, and the lantern’s immediately-apparent aura make an incomparably striking impression. However, Kojima Shōten is one of only two or three remaining Kyoto workshops that use the jibari-shiki method. Even as they shoulder the responsibility of carrying on this tradition, the two young craftsmen are constantly searching for new designs to suit modern lifestyles.

Shun Kojima

Born in 1984. With his straightforward and stubborn artisan’s temperament, Shun is in charge of the bamboo splitting part of the lantern-making process. Shun and his wife have a one-year-old daughter.

Ryo Kojima

Born in 1989. Ryo’s role in the lantern-making process is affixing paper to the lantern’s frames. His youth gives him a flexible sensibility and the ability to stand back from a situation, making him the one who maintains the balance in the Kojima family.

Parent and child, master and apprentice

In the Kojima family, the relationships between father and son, and master and apprentice father-son are actually one and the same. Mamoru’s paternal feelings towards Shun and Ryo, and his guiding instincts as their master, are completely indistinguishable. Teaching the skills of work is equivalent to teaching the skills of life, and inheriting tradition is the same as bringing up the future. Such is the nature of a historical family business.

Since Kojima Shōten has been family-managed for generations, the family home is the workshop, and so the workshop was where Shun and Ryo played as children. They recall being scolded frequently for getting in the way of the artisans’ work. Shun was in high school when he first helped with the family business as a result of an illness that caused his grandfather Toyokazu, the eighth generation master, to take an extended break from the workshop. It was just before the autumn festival season, the busiest time of year for Shun’s father and the other artisans. The grandfather’s absence at this time was a heavy blow for Kojima Shōten. Mamoru, the ninth–generation master, called son Shun to his debut with the words, “Hey, would you give us some help ?”

So it’s true to say that Shun never really put his hand up to be the successor to the workshop, but was brought in as a pinch hitter to help with the family’s work in a time of great need. They were too busy to even sleep, and day after day Shun, his father and the other artisans took naps on the floor between the lanterns they were working on. Shun recalls being astonished at the difficulty of the work, work that he was accustomed to seeing his father and the artisans carrying out so nonchalantly.

After graduating from high school, Shun officially began his apprenticeship at Kojima Shōten. Shun’s master was, of course, his father Mamoru. For the first three years Shun was allowed to do only the most basic preparatory jobs, such as shaving the cakes of ink used for decorating the lanterns. Shun repeated these monotonous tasks all day long. When he went to show his father his work, Mamoru would simply mutter, “Wrong” or “Useless, there’s no point even discussing it,” completely rejecting Shun’s work. Shun retaliated, demanding his father look properly at his work, only to be bluntly rebuffed. “I don’t need to look at it to know if it’s good or bad. I can tell by the sounds you make when you work”. In this way, Shun received no hints as to what was wrong with his work. Mamoru told him to “experience, fail, and think for yourself.” By repeating the same task over and over, you learn naturally by experience- this is the quickest way to learn. Shun’s father knew this from his own experience, and wanted his son to learn his craft in the same way. “My father didn’t teach me either” says Mamoru, looking straight at Toyokazu. The eighth-generation master silently watches Ryo at work on a piece, as if oblivious to the conversation around him.

Ryo began his apprenticeship about seven years ago. At that time, elder brother Shun was already advanced in his training, and allowed to split bamboo. Shun sat facing his father, watching and imitating how his father worked. Even at this stage he received no direct guidance. Shun failed at his first attempt to split bamboo, cutting his finger. Blood flowed. The pain served as a lesson, and Shun learned for himself the importance of giving his complete attention to a task. He felt he had finally started to understand what his father meant.

“You both just happened to be born into a family in the lantern trade; I never said you had to take over the family business. You grew up watching us work here. It was natural for you to think this was how you would live when you grew up. Of course I didn’t expect my sons to take over. I thought that my generation would be the last. Despite this, I was delighted when my sons told me they would take over the business. There aren’t really many places where parents and children can work together like this. I’m grateful to you two from the bottom of my heart. I wasn’t able to defy my father or express my own opinions, so I would like for my sons and I to be able to discuss anything. Well, that’s probably why Shun and I lock horns so often.

“Shun can already split bamboo twice as fast as I can. Ryo glues paper more beautifully than anyone else I’ve seen. I’m truly impressed that they have both picked up their crafts much quicker than I expected” Mamoru says, commending both sons’ progress. Shun and Ryo are embarrassed by the rare outburst. “Wow, this is just about the first time our father has praised us!”

How Kyoto lanterns are made

1.Bamboo splitting

First, pieces of bamboo are cut for the lantern frame. Suitably moist and flexible bamboo is selected based on the appearance of its skin. The bamboo is split into long strips in accordance with the size of the lantern to be made, and further split into narrower strips using a hatchet. This first step is mainly undertaken by Shun.

2.String hanging

Next, the bamboo bones are slipped onto a wooden form, and fixed firmly in place with hemp string to increase the strength of the frame. This step ensures the lantern will be solid.

3.Paper gluing

In this step, starch is applied to paper that has been moistened with a sprayer, and the paper is affixed to the frame. This step is primarily Ryo’s responsibility. As the paper used in jibari-shiki lanterns is relatively thick, the procedure in the paper affixing step is extremely important for achieving the desired texture.

4. Decoration

Characters or pictures, such as shop logos, temple names, or other patterns are painted by hand. Each design is produced in consultation with the customer, and painted directly on the lantern using a brush and ink .

5. Completion

Jibari-shiki lanterns are said to last at least ten years if used with care. The artisans take much pleasure in seeing their lanterns hung with respect in shops, temples, shrines and the like.

Lighting the city: Kojima Shōten’s lanterns around town

Lanterns made by Kojima Shōten can be found all over the city of Kyoto, including in front of a renowned theater, outside ryokans (Japanese-style inns) and guest houses, and decorating restaurants and bars. Spotting Kojima Shōten’s lanterns around the city might be a fun way to spend some time during your visit.

A. Minamiza (120cm x 185cm)

Located adjacent to Gion, Minamiza is a well-known theater that hosts kabuki performances and more. Not many locals would know that the Minamiza’s famous lanterns were crafted by Kojima Shōten, or that they were newly remade in December last year.

B. Kyōya

This inn has a lantern displayed at its entrance, and small lanterns used as foot lighting in the entrance way. Certified as a “baby-friendly” inn, Kyōya’s guest rooms feature Kojima Shōten’s washi-mari paper balls

C. Compass

The lantern at the entrance of the guest house Compass, a renovated 100-year-old townhouse, was also made by Kojima Shōten. Decorated with English letters, this lantern is popular for its fresh, modern look.

D. TaKaMaDo

The interior of this fashionable downtown-area bar features a unique lantern shaped like a cocktail shaker. This eye-catching shape lends an air of elegance to the establishment.

E. Isshindo

In a city with many famous ramen establishments, Isshindo is a particularly popular outdoor standing-style ramen shop. The shop is instantly-recognizable by its crimson Kojima Shōten lantern.

Upholding tradition, linking to the future

Even in Kyoto, where history and culture are held in high regard, traditional industries sometimes find that keeping business viable is becoming more difficult as times change. In light of this, in June last year Shun and Ryo launched a new brand, Kobishiya Chūbe, which features a new style of lanterns created to suit modern lifestyles. The name of the brand is a revival of the name given to the shop by its first master, Chūbe Kojima, some 220 years ago. They chose to use the original name of the shop to represent their concept of fusing the past with the future.

Both brothers strongly believe that traditions should not simply be upheld, but should also be updated with the times, since having more people appreciate the craft of the lantern will enable the tradition to be carried on naturally. Poised to soon officially take on the role of tenth generation masters, Shun and Ryo are writing a new page in the annals of their family business.

Chibi-maru【Small ball】

Kobishiya Chūbe also produces a small lantern, called the chibi-maru. This lantern was conceived of as one that could be used as everyday lighting in ordinary homes, not just temples and shops.

Kobishiya Chūbe holds workshops where participants can make their own chibi-maru to take home. These workshops provide an opportunity for people to appreciate the materials and textures with their own hands.

For inquiries and bookings: info@ko-chube.com

Washi-mari【Balls made of washi paper】

In the spring of last year, Kojima Shōten received a request from Kyōya Ryokan, to whom they had previously supplied lanterns, asking whether a baby’s toy that would be appropriate for a Japanese-style inn could be made using lantern-making techniques. After some trial and error, Shun and Ryo gradually rounded the shape, and, as a final touch, put a bell inside. The washi-mari, made from all natural materials and safe for babies to play with, was complete.