Jeff Berglund

International Goodwill Ambassador for Kyoto City, Professor of Intercultural Communication at Kyoto University of Foreign Studies, TV and radio personality, author, and English teacher

Table of Contents:

- 1969: Times of change-both global and personal

- First impressions of Japan

- 1970: called in front of the blackboard

- An arranged marriage with a Japanese woman

- Advice from a master and a son

- Living in a traditional machiya house, Jeff-style

- Japanese styles of communication, as theorized by Jeff

- Human relationships: Kyoto’s greatest asset

- Jeff’s Kyoto travel tips

- Be sure to watch Jeff’s YouTube channel

- 1 1969: Times of change-both global and personal

- 2 First impressions of Japan

- 3 1970: called in front of the blackboard

- 4 An arranged marriage with a Japanese woman

- 5 Advice from a master and a son

- 6 Living in a traditional machiya house, Jeff-style

- 7 Japanese styles of communication, as theorized by Jeff

- 8 Human relationships: Kyoto’s greatest asset

- 9 Jeff’s Kyoto travel tips

- 10 Be sure to watch Jeff’s YouTube channel

1969: Times of change-both global and personal

It’s a measure of how times have changed to note that when Jeff Berglund first arrived in Japan in the 1960s, only three or four universities in the United States offered Japanese language classes. It was a time in which one US dollar could be exchanged for 360 yen. Japan was still in the midst of post-war rebuilding, and was neither the economic superpower nor the tourist mecca that it has become since.

Hailing from South Dakota, in the middle of the continental United States, Jeff majored in Religion at Carleton College in Minnesota. At a job during one summer break, he became close friends with a Japanese exchange student, the first oriental person he had ever met. Upon returning to college the next semester, Jeff found out that the most popular professor of Religion on campus would be taking a group of students to Japan for a summer seminar. As luck would have it, Carleton had a sister school relationship with Kyoto’s Doshisha University, and Jeff signed up for what would be a life-altering experience.

And so in June 1969, as one of 26 students, Jeff first set foot in the city of Kyoto. Given the option of staying on until December, even after the seminar had ended, he and five other students elected to do just that. Doshisha University however, was at the time experiencing the peak of its student activism. The gates of the university were barricaded shut, and not once during his ‘study abroad’ period was Jeff able to get onto campus.

He and the other exchange students studied Japanese at the Nihongo Gakko, near the Doshisha campus. At the Kyoto University campus, students were running riot- overturning trams and smashing the windscreens of cars. Tear gas hung in the air, and clashes between student protestors and riot police in Tokyo even brought about fatalities. 1969 was indeed a turbulent year worldwide- with the staging of the first Woodstock festival, the release of the seminal movie Easy Rider and the Beatles’ Abbey Road, and the Apollo 11 mission successfully landing mankind on the surface of the moon.

First impressions of Japan

Jeff recalls his first impressions of Japan- unfamiliar aromas and a clinging humidity. For the first time in his life, Jeff experienced a change in climate. Having grown up in an area some 2500km from both US coastlines, he’d never once in his life had to use an umbrella. When he first arrived in Japan, he was greeted by tsuyu – June’s sodden rainy season. Wet shoes placed in a shoebox grew mold within three days. Mold itself was also a first for Jeff.

He looks back on the time as marked by the smells of people’s daily lives. In the US, his nearest neighbor three kilometers away, an olfactory presence of those around had never registered with Jeff. In Japan however, with neighbors just the other side of the wall, it’s possible to guess when company bonuses have been paid by the smell of sukiyaki wafting through from the house next door.

Jeff, who until arriving in Japan had not eaten much fish, admits to getting a shock upon his first sanma saury, head and all. Sashimi, sliced raw fish, posed another interesting dilemma. Jeff also found confusing the Japanese dining style, eating rice and okazu (main dishes) at the same time. Fish, rice, vegetables, rice, pickles, rice the standard style of eating. Now that he’s well used to this, he urges everyone visiting Japan to eat in this way to gain the most from Japanese cuisine.

1970: called in front of the blackboard

His study in Japan completed, Jeff returned to the US and graduated from Carleton College in the summer of 1970. At the time only able to read or write Japanese with effort, Jeff was invited back to Japan to help out Professor John Perry, his wife, and their five children settle in for a one-year sabbatical.

Professor Perry is in fact a distant relation of Commodore Perry, who in 1853 visited Japan in his ‘black ships’ and demanded that the country open its doors to world trade. Soon after Jeff and the Perrys arrived in Tokyo, however, an American teacher at Doshisha High School abruptly resigned, leaving a post which Jeff was invited to fill until a replacement could be found.

What was at first a one-month assignment stretched out month by month, and thanks to the pleasure that Jeff took in the work, and glowing acclaim from students and staff, it eventually turned into a 22-year stint. Going from instructor to tenured teacher, he was put in charge of his own homeroom classes. Attending meetings, he was given the same responsibilities and rights as Japanese teaching staff- something that made him feel right at home. It’s probably no exaggeration to say that the career break given him by Doshisha High School played a huge role in making the Jeff Berglund of today.

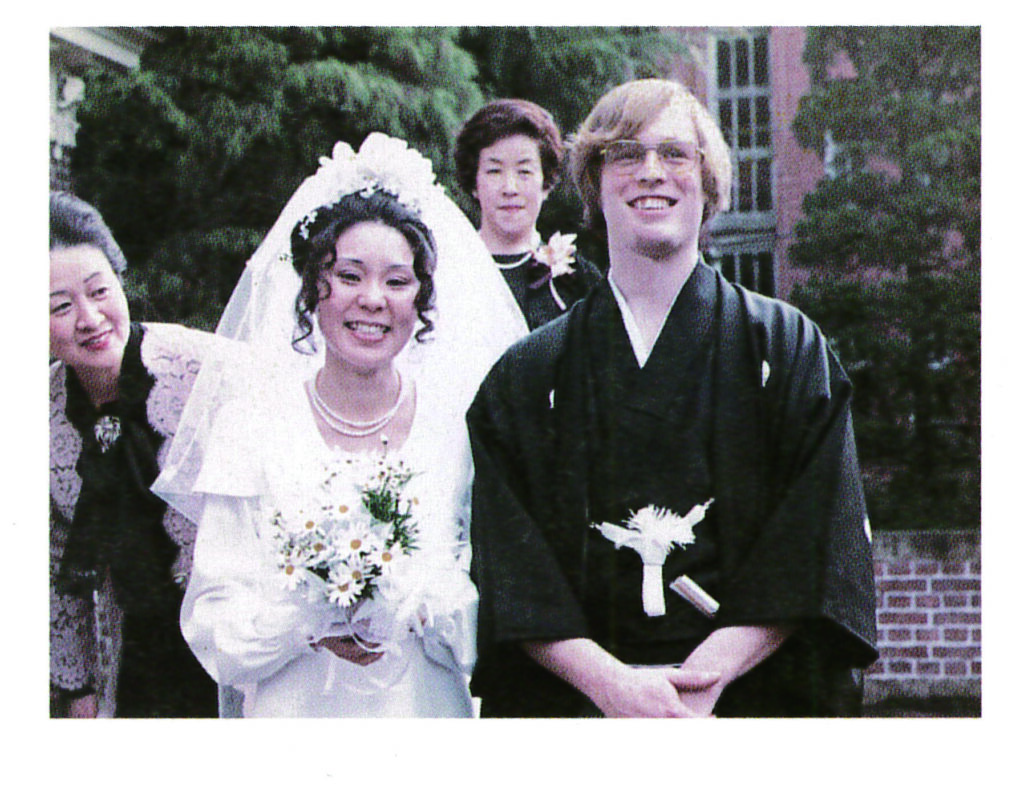

An arranged marriage with a Japanese woman

In 1972, Jeff did something which was a little out of the ordinary, especially for a foreigner- he had an omiai marriage. Omiai, or ‘arranged marriage’ as it is sometimes translated, is a custom by which two hopefuls are matched by an intermediary. This style of meeting a life partner is decreasing in Japan, but for Jeff it seemed a remarkably logical choice.

The reason for this is that at the time, marriage between Japanese and non-Japanese was nowhere near as common as it is today, and something of a difficult path. Jeff had witnessed personally the difficulty friends had marrying Japanese women without the blessing of the parents. But in the case of omiai, the families of both parties are part of the agreement from the start, so Jeff believed that there was little danger of being rejected as unsuitable by the parents.

Jeff gave the intermediary a list of the five characteristics he hoped his prospective wife would possess. First, she should to be able to speak English. Second, she should be a Christian. Third, he hoped she would be intelligent. Fourth, he wanted a partner who wasn‘t too concerned with looks. Finally, Jeff wanted to marry someone with a distinct personality. The woman who met all of these rather strict stipulations is his wife, Kaoru.

After graduating from Doshisha University, she went to work for a British trading firm in Kobe. Jeff and Kaoru have three sons- named Ken, Ryunosuke and Soseki, in rather Japanese fashion. Ken was, coincidentally, the name of both Jeff’s father and their omiai intermediary Akiyama Ken, but more importantly the name of the yakuza movie actor Takakura Ken, who starred in the movie they saw on their first date. The younger two sons are named for two giants of Japanese literature, Akutagawa Ryunosuke and Natsume Soseki. Jeff calls his wife Okāchan (‘Mom’) just like every other Japanese husband his age.

Advice from a master and a son

Jeff reached what was to become a huge turning point in his life around 1983. A friend working at a publishing company was impressed with Jeff’s fluent Japanese, and offered him the chance to put his words on paper and write some books. Jeff’s first effort, The Beatles, Once and Forever became the first educational material to be published based on the famous group, and became a best-selller, selling 40,000 copies in its first month.

Next was a book on the first foreign-born sumo wrestler, the Hawaiian-born Takamiyama. The book found its way into the office of the talent agency for Ohashi Kyosen, who at the time enjoyed fame as host of the popular TV program, “Sekai Marugoto HOW Much?”, and Jeff was promptly invited to be one of the foreign guests on the show’s panel. Offers to appear on TV, radio and other events soon flooded in. However, since Jeff was still a full-time teacher at Doshisha High School, he had to turn many of these offers down.

Considering a move to Japan’s media centre in Tokyo, Jeff asked another member of the Sekai panel, the world-famous film director Kitano Takeshi, for advice. Kitano warned him not to dive headfirst into the Japanese entertainment industry, calling it a ‘world of illusion’. “If you were to quit your teaching in Kyoto and come to Tokyo,” the auteur continued, “you might make in a month what you now make in a year. But you can’t be lured in by that. As an American, as a Christian, and as a teacher, you’ve got to make decisions based on your own solid convictions.’’

Jeff’s eldest son Ken, at the time a middle-school student, offered his own sage advice. ‘If you move only for money, you’ll only feel empty once it’s all over.’ Both opinions proved decisive, and Jeff never made the move to Tokyo.

Years later, over drinks with his son, Jeff remarked to Ken that his words of advice had been a deciding factor against the move to Tokyo. Ken admitted that he had racked his brains to come up with a line of reasoning that would keep his father in Kyoto because he, himself, didn‘t want to move to Tokyo. He figured something along the lines of “Dad’s not someone who’s in it just for the money” would work.

Based in Kyoto, Jeff has stayed true to his teaching profession, with successive positions at Otemae Women’s University, Tezukayama Gakuin University and finally his current professorship at Kyoto University of Foreign Studies.

Living in a traditional machiya house, Jeff-style

Jeff lives beside the Kamo River in a late-Edo period machiya townhouse, which was previously a ryokan. In 2000, having just moved into the house, Jeff had a rather strange experience. The 160-year-old building had needed some renovation, and tradespeople had been coming for the entire month before Jeff’s family moved in. The carpenters went home every night, but since he lived nearby and didn’t want to leave the house and all its lovely fittings unattended, Jeff elected to sleep in the machiya.

On his first night in the house, Jeff awoke to see a man and woman in kimono kneeling by his pillow. They wore not the finery of samurai and princesses, but the rough clothes of the lower classes. The pair disappeared instantly. Unsure whether it was a dream or reality, Jeff is sure about one thing- he was being welcomed to the house.

A month after he had moved in for good, a two-metre long white snake found its way into the machiya. It slithered out of the oshi-ire closet, did a circuit around the tatami-matted floor, and slid back into the oshi-ire as suddenly as it had come, never to be seen again. White snakes are considered household guardians in traditional Japanese lore, so of course Jeff felt something auspicious in this surprise visit.

Another time, Jeff was told by a clairvoyant that he had been an Edo-period samurai in a previous incarnation. It may sound fantastical, but even on his first visit to Japan, Jeff had experienced a deep feeling of déjà vu, even of homecoming. The sense of “I’ve been here before” may be connected with these other extraordinary happenings.

On the appeal of machiya houses, Jeff gives the following reasons: communication with people, communion with nature, and connection with time.

First, let’s look at what he means by human communication. Machiya are usually built in a terrace style, which means your roof touches the roofs of your neighbors on both sides, and also that rain from this shared roof runs to all downpipes equally. According to Jeff, being able to negotiate this communal space, and cherish the relationships which develop there, is the key to living in a Kyoto machiya.

One example of this is the importance of never complaining directly to anyone- it’s imperative to always voice your grievances through a third person. “In Kyoto, you’d make an offhand remark to the greengrocer such as ‘I’m having a bit of trouble with the people next door.’ And next time your neighbor was in the shop, the owner would mention in a roundabout way that there was something that you wanted them to know was troubling you.” It’s very Kyoto- so soft and indirect. But this is part of the culture of living in this city.

Machiya need constant maintenance, and the carpenters coming in and out of houses provide another route of communication. Your carpenter passes on a message to your neighbor’s carpenter, who in turn communicates it to your neighbor. In this way, you can still give your neighbor a smile and a greeting in the street, without having sullied the relationship with any direct negativity,” laughs Jeff.

Communion with nature is another focus of machiya life. Kyoto experiences blistering summers and frigid winters. With stone floors in some rooms, machiya feel the cold especially severely. Jeff doesn’t see this as essentially bad, however. Four distinct seasons is a hallmark of Japan, and especially in Kyoto, with its abundance of food, sweets, festivals and the like created to savor the changing of the seasons.

The Japanese are said to be a non-religious people, but Jeff sees the opposite as true. Japanese culture places gods everywhere and in everything. Jeff’s mother-in-law told a memorable story, based on the idea that the gods of the mountains are angered by humans digging tunnels through them. She was taught that every time she passed through a tunnel, she had to clasp her hands in prayer and whisper “God of the mountain, please let us pass through your tummy!”

Freshly arrived in Japan, Jeff was taught by his rooming house mother that he should pray facing to the east every morning: “Thank you Tento-sama (Mr. Sun), for giving us this day!” “All Kyotoites do this!” she insisted, when Jeff asked about the ritual. Even as Japan modernized and joined the world’s developed nations, Kyoto was, and still is, a place where you can find people clinging to spiritualities such as these.

Finally, the concept of connection with time. “Living in a place like this, you’re constantly required to adopt a traditional lifestyle,” says Jeff. “That’s only natural when you consider that most machiya have seen far more of Kyoto’s history than the majority of their inhabitants. My house has been here for over 160 years.” That kind of longevity brings about a kind of natural awe from those who live in or visit these homes. “For example, there’s a nick in the wood- that was made before I was even born. The fact that someone was here caring for this house before me is in a way, a kind of indirect link, a form of communication.”

Living in Kyoto is about contact with others, cherishing the seasons, and a sense of the passage of time. The old-style calendar hanging unceremoniously on the wall speaks to this important truth. Jeff remains a part of this place, continuing his university teaching and research, his writing, and his private English school.

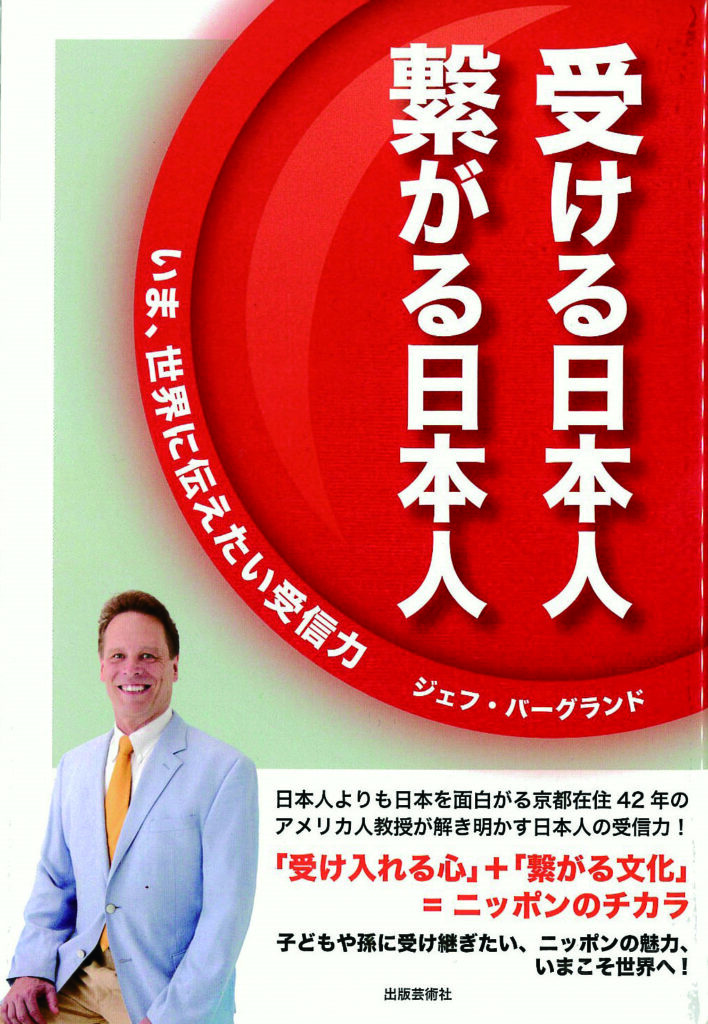

Japanese styles of communication, as theorized by Jeff

Jeff has a theory of communication, formulated over 45 years of living, researching and teaching language and culture. It concerns the binary of sender responsibility and receiver responsibility. English is a good example of a language that places emphasis on sender responsibility- the idea that the sender of a message, for example, a Hollywood movie director, has a duty to provide a clear, unambiguous message. That is why children in the West are generally raised to be good, active communicators.

On the other hand, receiver responsibility is about reading the signs; being able to understand often subtle forms of communication, which are more prevalent in societies such as Japan. One of the features of the Japanese language is its avoidance of pronouns. According to Jeff, this is one of the hallmarks of receiver responsibility. When you don’t use a pronoun, the listener must still be able to understand the person or thing you are referring to.

Jeff gives an example. When a Japanese speaker says “Went to Osaka yesterday” the listener knows instinctively who it was who went. This is because of the cultural background of receiver responsibility shared by speaker and listener. Jeff believes that Japanese culture is the most receiver-oriented in the world. Reading the clues of context, time, and facial expression- these are some keys to understanding Japanese communication.

When an American is learning Japanese, they will often do this by asking “How do you say this English phrase in Japanese?” This is not the best way to learn, warns Jeff. He picked up his Japanese by instead imitating the Japanese used by those around him. Even before perfectly understanding the meaning of phrases, using them in the same way and in the same context as native Japanese speakers is the fastest route to fluency.

For example, Jeff learned the phrase ittekimasu (lit. “I’ll go and (then) come back”) as something you say in the doorway as you leave the house, without really analyzing its meaning. On returning to the house, one says tadaima. He repeated this every chance he got. Of course, he made some mistakes along the way.

His Japanese friends at the same lodging used the phrase osaki-ni whenever they went downstairs to have a bath, so Jeff naturally thought it meant, “I’m off to have a bath now”, when in fact it means something like “excuse me for going first,” which must have been strange when Jeff, who was always studying Japanese until late at night, said it before using the bath last of all. On top of that, when a kimono-clad old woman said osaki-ni before getting on a bus in front of him at a bus stop, Jeff thought she was making a joke, perhaps playing on the identical pronunciation of bus and bath in Japanese.

Arriving back at his lodgings, Jeff told the story in his convoluted learner’s Japanese to his friend (who, incidentally, later became Vice-President of Kyoto University of Foreign Studies), the penny finally dropped on his misunderstanding.

This experience was the one which first alerted Jeff to the differences between the differences in communication styles of Americans and Japanese. In sender-centric English, clipped, context-dependent phrases such as osaki-ni are so rare as to not exist. The equivalent of the phrase osaki ni dōzo exists (Please, after you….) , though this is used mostly as politeness towards a specific person, such as a pregnant woman, an elderly man, or someone with an injury.

If one is to go somewhere before someone else, then a phrase signifying this is unnecessary in English. The behavior of going first sends a clear message, (I’m going first), Japanese must read the situation and the feelings of those around them, whatever the situation. This fact was a huge discovery for Jeff at the time.

Asked by a Tokyo publishing house to write a study comparing Japanese reactions to the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, and the reactions of victims of other natural disasters, Jeff made some notes. Where some would talk about the patience and stoicism of the Japanese, Jeff resisted these labels.

“Well, these things exist in other cultures as well. I wanted to think about this idea from a receiver vs. sender point of view. People from sender-centric cultures in a situation like this, say at an evacuation site, would send the message “I‘m thirsty” by elbowing other people away and grabbing the water. But Japanese evacuees, being from a receiver-centric culture, would find out who needed water the most before doing anything. That’s how I saw the difference in behavior.”

Kyoto people are the most strongly receiver-centric of the Japanese culture overall, claims Jeff. This is reflected in the ways in which subtle nuances color the speech of everyday life. Here’s a famous example. When your neighbor in Kyoto tells you that your grandson is really coming along well in his piano lessons, thanking them for the compliment is not the correct response. What you’re supposed to say is “Sorry for making so much noise.” This is the epitome of receiver responsibility. You’re supposed to read the background of what is actually being said, which is not always an easy task for someone from another culture.

Both English and Japanese feature a formidable inventory of over 100 verb conjugations, though in English these are mostly related to time, and changing conditions. Japanese verbs, on the other hand, vary predominantly to reflect human relations. Your status relative to your interlocutor, and how you relate to others, are key. English is relatively explicit and direct about things. Japanese is relatively explicit and direct about relationships. This is something that is vital to communicating in the language- the fundamental component of intercultural communication that Jeff discovered over his many years of living in Kyoto.

Human relationships: Kyoto’s greatest asset

For Jeff, the greatest appeal of this city will always be the relations among people. Kyoto in the past was the kind of place where the bookstore staff would not only greet you warmly by name, but remember that you were a philosophy enthusiast, and recommend a rare book by Kant that had just come in. In some of the older shopping streets, you had miso shops selling ten different types of miso, from ink-black to snowdrift-white. Across the street stands a greengrocer’s. You buy a daikon radish from them, and ask the owner what kind of miso would match its flavor, were you to make miso soup. The greengrocer crosses the street, confers with the miso seller, who brings you some of the third-lightest miso with a “This one’s perfect!” You take home the daikon and miso chosen for you, and make a superb miso soup.

Living in Kyoto for 45 years, Jeff has been part of this kind of local exchange on countless occasions. But he fears that it is something disappearing from the city. Mukō sangen ryōtonari (three houses across the road, neighbors both sides) is an old phrase that names the people with whom one should keep cordial relations. Back in the day, when a new shop opened in Kyoto, the owners would make the rounds of the neighborhood introducing themselves. With the recent influx of stores and chains from Tokyo and elsewhere, Jeff laments that many newcomers ignore this custom.

On the other hand, he feels that Kyoto is an extremely welcoming place for non-Japanese. “It’s especially kind toward those who don’t live here long,” he grins. That’s why university students are welcomed here, too. It used to be that most foreigners living here were university professors or language teachers, but these days Jeff notes the increase in painters, musicians, dancers, writers, and poets making Kyoto their base.

“If you are teased or scolded by a local, wear it as a badge of pride. It’s a sign you have been accepted as a resident of the city,” Jeff asserts.

Jeff’s Kyoto travel tips

After almost a half-century in this city, Jeff would be one to ask for some advice on places to visit. His answer is simple: “Walk all you can.” And since Kyoto is a city ringed by mountains, they’re also a place he wants all visitors to explore.

Take the northern Kitayama area for example. It’s only 20 minutes from Kinkaku-ji temple to Ryoan-ji temple on foot, and a further 15 minutes to Ninna-ji. That’s three stunning temples (three of the seventeen World Heritage sites in Kyoto) all within easy walking distance of each other. Through the gates of Ninna-ji, the twin hills of Narabi-ga-oka are beautifully framed, and this spot is another favorite of Jeff’s.

Next is the Higashiyama mountain range in the east. The solemn air of Mt. Hiei and Enryaku-ji at its summit feels a world away from the bustle of the city below, and is well worth the climb. Another mountain escape is the hike up from Ginkaku-ji along Daimonji-yama to Nyakuōji, to the grave of Doshisha founder Niijima Jō. The route from Ginkaku-ji to Kiyomizu is lined with a multitude of famous temples, and it’s a pleasant diversion to peek into these as you stroll.

Finally, the western Nishiyama walk would have to include Arashiyama. Jeff says that it’s about 10 kilometres between Matsuo Taisha in the westernmost end of Shijo-dōri street and Yasaka Jinja at the eastern end, and talks of the delight of a two-hour walk between the two.

Jeff stresses that it’s important not to forget the walks in one’s own neighborhood. After walking the shopping malls, Teramachi Street arcade , or Nishiki Market, a walk around one’s local shopping street is the best way to appreciate the true atmosphere of the locals and their city. Kyoto has a number of wonderfully quiet streets and lanes hidden just off its main thoroughfares, and it’s here that you’ll find the city’s beating heart. You’ll stumble across temples and shrines not listed in any guidebook. On a rainy day, walk beneath a traditional bangasa umbrella. The smell of the umbrella’s oil mingles with the smell of the rain. And on days like this, fewer customers in shops means you can take your time to savor the discoveries of the streets.

“The best way to appreciate this city is to do as the locals do, and slowly, slowly walk its streets, take in its sounds and smells,” Jeff gently suggests in his lilting Kyoto accent.

Be sure to watch Jeff’s YouTube channel

Jeff has his own channel on YouTube on which he posts videos of famous spots around Kyoto, its culture and lifestyle. Travellers to Kyoto will find a wealth of information to make their trip much more meaningful