Elevating art and calligraphy through masterful reframing

Welcome to the art of hyōgu, meaning picture mounting or paperhanging. It’s a field that is perhaps unfamiliar to many, but could very well be considered one of the most Japanese of traditional crafts. Hyōgu is a traditional technique used to create folding screens and fusuma (sliding doors) decorated with artwork referencing the season in temples and shrines. These folding screens and fusuma are changed regularly to reflect the colors and motifs of the season. Most Japanese homes are designed with a tokonoma; a wall recess where flowers and artwork are displayed. The vertical scrolls hanging in the tokonoma of some homes are also created with hyōgu techniques. To this day some families observe the traditional custom of replacing the hanging scroll in the tokonoma at New Year, or celebrating the arrival of the new year by displaying an appropriately splendid scroll during the New Year period.

So, if the calligraphy or painting is the “star” of the artwork, hyōgu is the “supporting actor”, quietly working on the sides and allowing the “star” to shine. The role of the hyōgu-shi (picture mounter) is, then, to create a scroll or screen using paper, fabric and other materials that brings out the best of the artwork. Although in some respects it might be akin to framing in Western art, hyōgu is incomparably diverse and intricate in terms of expression. You could say that hyōgu a process of bringing a new viewpoint to a piece of art – reframing its entire world.

The history of hyōgu can be traced back to the arrival of Buddhism in Japan in the middle of the sixth century. At the time there was, of course, no satellite TV, no email, no file transfer services, and no YouTube. For the teachings of Buddha to make their way across the ocean from China to Japan, they had to be brought in the form of sutras written on scrolls called kyōkan, or sutra scrolls. The sutras were written on paper and mounted on scrolls to prevent damage and deterioration. This is said to be the beginning of the hyōgu tradition as we know it today. In China, hyōgu techniques were used simply for preserving writing and art. It was only after its arrival in Japan that these techniques gradually came to take on a decorative role. In other words, hyōgu as an artform might be said to have begun in Japan.

In the ancient capital Kyoto with its wealth of cultural knowledge, there was a need to preserve the writings of Emperors, the aristocracy and samurai. This, combined with its flourishing culture of arts such as calligraphy and painting, meant that Kyoto was the ideal place for hyōgu to truly blossom as a field. The original purpose of hyōgu, as mentioned above, was to preserve calligraphy and pictures inscribed on delicate paper that would not otherwise survive the passage of time. Calligraphy and paintings were mounted on backing paper or folding screens to reinforce and preserve them in order they may be read or enjoyed by future generations. It is because of these techniques that many such folding screens and scrolls survive even now, handed down from generation to generation while being expertly restored by the hands of the hyōgu-shi of Kyoto. The beautiful works of art on folding screens, sliding doors and scrolls that we can see in the museums, exhibitions and books of Japanese culture have invariably been embellished by a hyōgu-shi. No doubt you’ve seen their work without even realizing it. That’s the mark of a truly great supporting cast- allowing the star of the show to excel, without drawing attention to themselves.

The roots of hyōgu-shi Masahiro Inoue

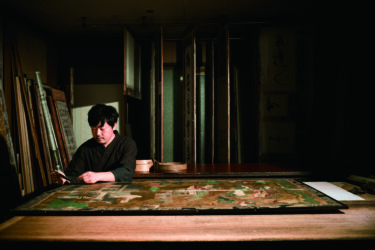

In the world of hyōgu with its long history, the spotlight is currently on Masahiro Inoue, a rising talent among the new generation. Inoue is a third-generation hyōgu-shi based at Inoue Kōgadō, a workshop near the famous Fushimi Inari shrine. As the name suggests, it’s a family affair. The workshop was founded in 1957 by Inoue’s grandfather, who worked for many years at Kyoto National Museum specializing in artifact restoration. Inoue’s father subsequently took over the studio, and it was in this environment that Masahiro was born and raised.

This meant that for the younger Inoue folding screens, sliding doors and hanging scrolls were a part of his life from a early age, and he grew up with the sound of scraped washi in his ears and the smell of paste in his nose. Inoue became interested in painting as he grew older, and his home provided the best inspiration and access to art he could have wished for. Because of this, Inoue never felt any desire to follow any other career path. Soon after graduating from junior college, Inoue declared to his father his intentions in becoming a hyōgu-shi to his father. In this way, much as a picture quietly blends with the folding screen it decorates, Inoue slipped into his career as a hyōgu-shi in the most natural way. He was twenty years old at the time.

Despite the fact that his father’s hyōgu workshop was part of their home, Inoue’s first step in training as a hyōgu-shi took place elsewhere. Inoue became a live-in apprentice under another hyōgu-shi, working alongside other artisans. Why did Inoue choose not to be taught by his father? He explains it best himself. “Hyōgu encompasses many different types of work. Because my grandfather had worked at the Kyoto National Museum, the bulk of the work our family handled involved restoring works kept at museums and temples. But it’s becoming harder to make a living solely from restoration, so I decided to first train under a hyōgu-shi who is taking on the challenge of working with relatively modern Japanese painting and creating new pieces. ”

After six years of apprenticeship, Inoue returned to his father’s workshop where he continued his training in becoming a hyōgu-shi. Inoue is now thirty-nine years old. He already boasts a career of nineteen years in the field, and has amassed a considerable back catalogue of countless stunning works. These days, Inoue is commissioned by a mix of long-time clients; some served by the workshop since his father’s time, and some from an increasing base of new clients, primarily modern artists, cultivated by Inoue himself.

Always thinking 100 years ahead

Let’s take a brief look at how a piece of calligraphy or a painting becomes a scroll in the hands of a hyōgu-shi. This is process carried out by the hyōgu-shi is as follows. The original calligraphic or painted artwork, called a honshi, is dampened with water to stretch the fibers of the paper. Next, specialized hyōgu paste is applied to a separate piece of washi, and this washi is attached to the back of the honshi. This is process is called urauchi, and is designed to prevent the honshi from degrading over time. After urauchi, the honshi is left to dry. When the honshi is dry, the urauchi and drying steps are repeated two or three times. Next, the washi applied in the urauchi process is carefully rubbed with a piece of soapstone or a string of stone rosary beads in order to soften the paper and prevent it from curling when the scroll is rolled. Next, paste is applied to the front surface of the backing paper and dried. When the paste is dry, any protruding parts of the backing paper are trimmed off. Finally, the top and bottom ends are wound around crosspieces to create the scroll. Each piece of backing takes several months to complete. It’s an extraordinarily intensive process that requires infinite patience and skill.

The basic backing work described so far is merely the tip of the hyōgu iceberg. In addition to the obvious functions of reinforcing and preserving works of art, another aspect of hyōgu is storage techniques. An art scroll must be able to be rolled up and stored away outside of its season, and so must a screen be folded up and packed away. This means the paper in a scroll must be rubbed to make it supple and prevent wrinkles when rolled, and the paper hinges of a folding screen must enable the screen to be folded easily. Some of the most time-consuming and difficult aspects of the hyōgu-shi’s work is in details such as this, that aren’t necessarily obvious to the onlooker. The humid Japanese climate presents additional challenges. So as to prevent stiff bumps forming in the finished product, hyōgu-shi must blend the paste to a precise consistency, and select the perfect type and thickness of washi paper. This is for Inoue however, one of the real pleasures of being an artisan.

“You base your decision on the sensation the instant you touch the paper. It’s not a skill you can be taught. In the same way that paste gradually soaks into washi, it’s something you learn gradually from your failures over a long period of time when you’re young. It’s not something a machine can do, and it’s different each time depending on the materials you use, so it can’t be quantified. The time it takes to dry the paper also depends on the humidity level. A succession of rainy days will extend the number of days it takes to complete a work. Simply drying a work can take at least a month. That means it will take a long time to complete a piece, and there will be a huge amount of effort involved. But, since we’re making artworks to last 100 years, we can’t allow ourselves an hour or two of carelessness or a rushed job. That’s the world we’re working in.”

Like so many other craftspeople of the traditional arts, Inoue straddles generations and eras. He leads a life in the contemporary world that is colored by people from the distant past, while producing work that will connect to a future far beyond his own lifetime.

The Japanese concept of beauty in function

As with most traditional arts, there are many established rules in the field of hyōgu. Hanging scrolls, for instance, are made based on the assumption they will be hung in temples or homes designed in the traditional sukiya style of architecture, which has predetermined basic dimensions and shingyōsō (levels of formality). There are also other minute and detailed rules. “There’s not much room for fun,” laughs Inoue. But the artisan’s propensity is to inject something of his own personality as skillfully as possible while still adhering to the countless formulaic rules. Inoue finds great joy in discovering the artisan’s personal touch in old artworks and works that come to him for restoration. Selecting a pattern that fits with the motif of the honshi for the top layer or making an interesting choice of material when selecting washi or fabric are ways in which a hyōgu-shi can enjoy adding their personality to the work. Finding a place to infuse some creativity is a part of the appeal of hyōgu and the key to its artisanship.

“Hyōgu itself is not the art, it’s an embellishment that enhances a piece of art. So, while it’s not strictly essential, it’s a form of expression that elevates the piece of art by its presence. The basis of hyōgu is the functions of preserving and storing, so the artistic aspect is incorporated for fun and expression. As with most of the traditional Japanese arts, hyōgu exists primarily on the basis that it is a necessity in everyday life. Then, because a purely functional object is boring, we add some creativity in the design or style. That’s what I think the true value of hyōgu is.”

When we look at a scroll or folding screen, most of us undoubtedly focus our attention on the calligraphy or painting in the center. Next time you see one, take a moment to appreciate the mounting supporting the main feature. You’ll find there an art that is quintessentially Japanese, something that is strikingly meaningful, and at the same time wonderfully expressive.

Framing the present for a century from now

There is of course a clear reason why hyōgu-shi Masahiro Inoue is gaining some attention despite working in a decidedly “behind-the-scenes” craft. Rather than limiting himself to traditional restoration work, he is actively involved in a variety of genres, such as contemporary and street art, and even wall decoration in commercial facilities and the latest hotels.

Deeply interested in music since his student days, during his hyōgu apprenticeship Inoue spent his nights as DJing at a local club, a place where he had numerous opportunities to brush shoulders with modern artists. He says the connections and ideas gained through this after-hours interaction provided him with inspiration for new directions for hyōgu.

“A DJ is neither a composer nor a performer,” he notes. “A DJ collects finished music sources that have been produced by talented artists, and selects and edits them to make his or her own individual remix. I felt that this is exactly like what a hyōgu-shi does.”

In fact, hyōgu involves using materials that are finished pieces of art in and of themselves, such as kimono fabric created by Nishijin-ori silk weavers and washi produced by paper artisans, and fashioning those materials into decoration. Furthermore, the criteria for each choice vary depending on a variety of factors, such as whether the end product will be a screen or a scroll, whether it will be displayed in a temple or a private house, the size of the artwork, and whether the style is modern or classic. It’s a world where there is no one right answer. And it must be remembered that hyōgu is merely a supporting actor. It must neither overpower nor subtract from the calligraphy or painting that is the star of the artwork. That’s exactly like a DJ, who also must elevate a pre-existing artwork to a higher level. These are the interesting parallels Inoue draws between the work of a hyōgu-shi and a DJ.

The concept of remixing, a central part of modern art, is a sensibility Inoue is actively incorporating into his traditional field. He has produced new styles of hyōgu in collaboration with a new generation of artists across several fields, including street artist Bakibaki and calligrapher Tomoko Kawao, whose work features in our own Enjoy Kyoto kanji masthead. He’s continually looking for new avenues for hyōgu techniques.

As Inoue explains, “washi was originally hung on the interior walls of Japanese homes, but these days most people use wallpaper. It would be interesting if we went back to using washi again. I’ve been engaged in that kind of work after being approached by clients wanting to use washi for the interiors of hotels, cafes, guest houses and the like. It’s very stimulating work.” Inoue says that eventually he would like to decorate an entire tea-ceremony room.

He has exhibited his work overseas, including in Dubai, France and Hong Kong, and is eager for hyōgu become better-known outside Japan. While ‘star’ art such as calligraphy and ukiyoe is popular overseas, hyōgu remains relatively unknown, and indeed, it is probably safe to say that few people are even aware that hyōgu artisans such as Inoue exist. Inoue continues to search for ways to promote a greater worldwide appreciation for the “delicate, understated expression” of hyōgu, 1600 years after it crossed the ocean with Buddhism to Japan.

Hyōgu, this most traditional of arts, is being reborn with the modern sensibility of Masahiro Inoue, in an exquisitely balanced remix of past and future, East and West, and tradition and innovation. His fresh take on the genre imparts a sense of deja vu and surprise all at once. And perhaps it is actually the worlds of Japanese traditional culture and modern art themselves that are being reframed by his steady hand.

【wall design at Kushuku Kyoto Hostel】

collaboration with contemporary street artist Jun Inoue

The ‘now’ through hyōgu – Masahiro Inoue’s recent work

Unfortunately, Inoue’s work is somewhat inaccessible, due to the fact that most of the screens and scrolls he produces are privately owned by temples or individuals, and even those on public display are brought out and stored only seasonally. The few examples of Inoue’s work that are permanently displayed include a mural in the basement of Sanjo Ohashi Starbucks, screens and sliding doors inside the Aoi Hotel Kyoto, and some decorative walls at Kushuku Kyoto Hostel. Instead having to hunt down his elusive works, here we’ll introduce some examples of his more innovative pieces.

Hinoki no Kazari, 2016

【scroll mounting】

collaboration with Hanaya Mitate

This emblematic work graces the cover of this issue of Enjoy Kyoto. Hanaya Mitate’s three-dimensional work is adorned with a real sprig of Japanese cypress and mounted within Inoue’s hanging scroll. The depth provided by the cutaway panel and the delicate Nepalese paper used for the scroll make this a work arresting in its modernity.

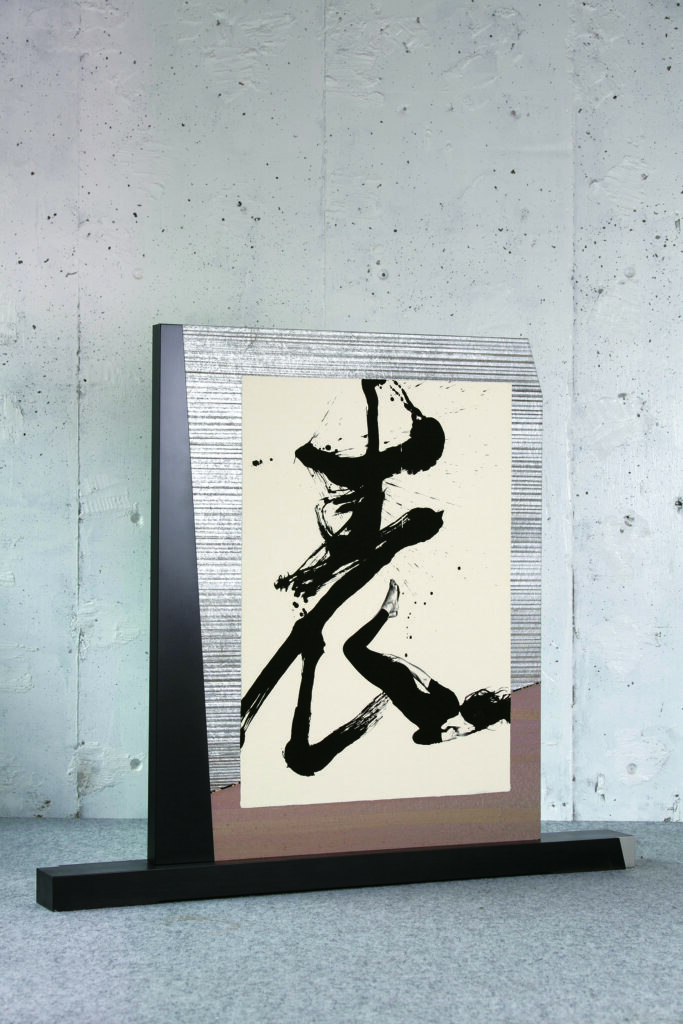

Hyo-ri, 2015

【screen with calligraphic work】

collaboration with calligrapher Tomoko Kawao

The kanji logo for our very own Enjoy Kyoto was written by Kyoto-based calligrapher Tomoko Kawao, whose twin works Hyo (meaning ‘front’) and Ri (‘back’) are mounted on the respective sides of this partition. The concept is to illustrate through lettering the two aspects of the space one enters and leaves within a room.

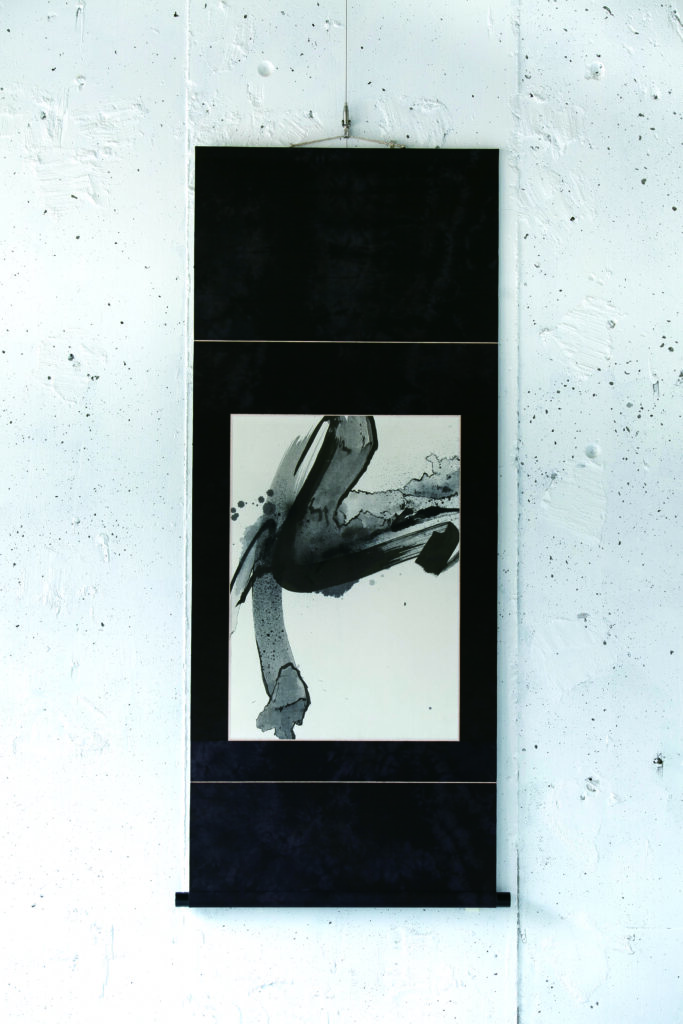

Untitled, 2013

【hanging scrolls】

These hanging scrolls were created from embroidered tenugui towels for Kyo-to-to, a local fabric and embroidery seller. The three auspicious New Year’s designs featured are the shōchikubai (Pine, bamboo and plum), the hana-musubi celebratory knot, and the tsurukame (crane and turtle).

Untitled, 2015

【hanging scroll with candle】

A collaborative work made for Japanese candle-makers Daiyo, with an inventive design featuring an actual lit candle. The candle sits regally in the space usually occupied by art or calligraphy, set well back from the scroll to offset the risk of fire.

Untitled, 2014

【hanging scroll】

Inoue gave this Nishijin-ori silk a deliberately uneven dying to bring out texture in the scroll mount for the work by street artist Jun Inoue.

Untitled, 2016

【folding screen,and other interior fittings】

Inoue restored the antique folding screen, sliding fusuma panels and hanging scrolls owned by the machiya-style guesthouse Aoi Kyoto Stay. He created a new look for each piece to better match the feel of a contemporary hotel.

Beyond Nishijin, 2016

Inoue’s entry in the World Art Dubai 2016 contest, this series of framed works is created from the highest quality Nishijin-ori silk. Each piece is embossed with silver leaf using the yakihaku technique of baking and oxidizing usually used in decorating fusuma and other fittings.

Maiko, 2014

【frame】

A fusing of the art of hyōgu-shi Inoue and street artist Zenone, this work is made up of a stenciled maiko motif spray-painted over a gold-leaf background. The border features traditional materials of a silk kimono obi and sleek black lacquer.

Untitled, 2015

【hanging scroll】

As a work for the tea masters Shuhally, Inoue crafted an anime-inspired scroll to frame street artist 2yang’s playful image of the Shichifukujin, or Seven Lucky Gods. The silk-screen printing on washi paper is an innovative approach.

Fūrosaki Byōbu, 2015

【folding screen】

Street artist Bakibaki contributed the bold, pop-artish design for this screen using the everyday tools of colored pencils and Posca marker pens. The subtle contrast between the black washi paper and the even blacker lacquer frame give the traditional teahouse screen a fresh modern feel.

Untitled, 2013~2014

【window display】

In collaboration with calligrapher Tomoko Kawao and street artist Hitotzuki, Inoue created an enormous artwork for the façade of the Panasonic Center in Osaka’s Grand Front building. Using Panasonic’s own LED lighting and creased washi paper to create shadows and space, the result is a beautiful marriage of traditional materials and modern techniques.

Untitled, 2016

【wall design】

Inoue’s latest creation is the striking entrance wall in the Rakuraku-an Boutique Hotel, just opened in Kyoto this past December. With the idea of ‘aging beautifully’ in mind, he opted to use aluminum foil rather than the standard silver as the background. With input from the hotelier, a former kimono store owner, Inoue brought together four diverse patterns on the highest-quality silk into a strip the width of an obi sash. This striking focal point is yet another of Inoue’s masterful blending of traditional and contemporary.