Japanese teaware created from the earth, water and soul of Uji

The Asahi-yaki pottery kiln has sat at the foot of Uji’s Mt. Asahi for close to four centuries. It’s believed that it was established just before the dawn of the Edo Period under a commission by Enshū Kobori, who assigned the kiln its Asahi (朝日) trademark. As an acolyte of the tea master Oribe Furuta, Enshū was a chajin (‘tea person’) the period’s equivalent of an artistic producer. Perhaps his greatest legacy to the Asahi-yaki name was his espousal of a unique kirei-sabi aesthetic, drawing refined beauty out of rustic, humble simplicity. Four hundred years after it was founded during the era of samurai lords such as Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Uji’s lone Asahi kiln continues to produce captivating pieces in the same distinctive style.

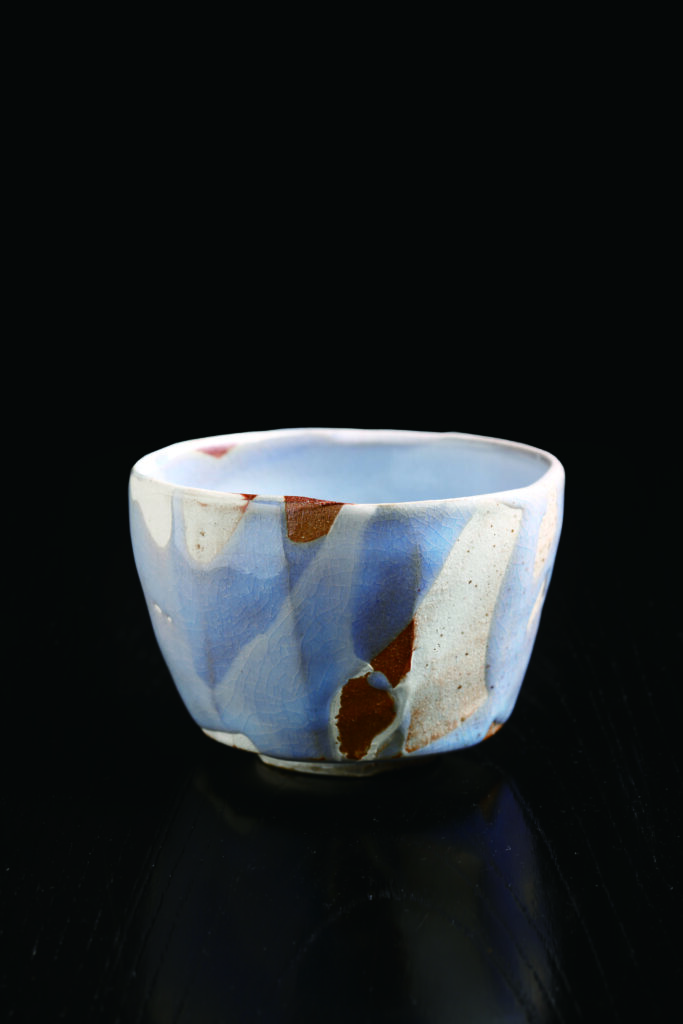

The concept of kirei-sabi is difficult to actualize, even for Japanese natives. “It’s about a duality,” says the former Yūsuke Matsubayashi, who last year at the tender age of 36 inherited the Hōsai name and the title of kiln master from his late father. With his younger brother Toshiyuki he has only recently accepted the baton passed down through the generations, and as a potter is just out of the blocks, so to speak. Five years ago he formed a project unit with a group of similarly-aged artists and craftspeople. Together they travelled around Japan exhibiting and marketing their work, which included collaborations with overseas artisans. “Kirei-sabi is a Confucian duality of the root and the flower, the pairing of primitive emotion and ornate beauty” he elaborates. In pottery form, you can see this in a single Asahi-yaki tea bowl combining the hallmarks of Kyoto’s most famous pottery styles; the unevenness of hand-formed Raku Ware and the magnificent color and form of Kyō Ware.

Hōsai believes there are three factors that are essential to maintaining the unique legacy of Asahi-yaki. First, the kiln must continue to produce pottery works that are born of and unique to the local area of Uji. Secondly, the raw clay used in Asahi-yaki must all be sourced locally. Finally, the kiln must be wood-fired to produce the pottery’s distinctive quality. In other words, Asahi-yaki Ware is not defined by any particular defined shape or color, but in the potter’s material and processes.

The Uji clay used by the potters has found its way through to the Uji River basin from the ancient soils of Lake Biwa, Japan’s biggest lake. It is as rich in iron as it is sand, and is a distinctive white in color. The clay is sticky and easy to shape, making it ideal for even delicate forms.

Hōsai creates his work from this clay on a wheel and fires it in an enormous kiln fired with sticks of split pine timber. The genyō kiln was designed and built by the 14th generation kiln master, the Matsubayashi brothers’ grandfather. Only lit an average of twice a year, the kiln looks comething like an enormous creature from a Studio Ghibli animation, with all manner of thick pipes, tunnels and stovebellies making up what are obviously ingenious firing devices. This creature waits patiently to be given its life-breath of fire, so that it may give birth to spirit in the form of bowls and cups.

“It’s terribly exciting, but I’m also a little edgy whenever the kiln is lit,” admits younger brother Toshiyuki. “We fire between one and two thousand pieces at a time, and there’s always the possibility that a whole batch will come out ruined.” In such an enormous kiln, there is an exact pattern of placement for each type of bowl depending on variables such as temperature, intensity, timing of stoking, and amount of firewood. Of course there are detailed records of every previous firing which are consulted as a guide, but since every time the kiln is lit under different conditions, the specialist instruction of the kiln master is invaluable as the artisans work night and day tending to the fire. Fluctuations in outside temperature, humidity, the condition of the kiln and quality of the clay all affect how the pieces turn out. But since the kiln reaches a temperature of 1300 degrees Celsius for up to five days, in the end all that the kiln master can do is entrust the work to the kiln and its flames. It’s possible to understand just how sacred a place the kiln is for all who work there when you catch sight of the enormous shimenawa straw rope and the candle lit lanterns.

The beautiful Asahi-yaki ware is created in this curious space between diligent action and stoic acceptance. The colors born from fire, Uji clay and traditional kiln knowledge are complex and captivating. Each piece is imbued with a pure sense of sanctity, and the hues produced are stunningly reminiscent of the asahi rising sun.

benikase herame chawan

‘deer-fur red’ mottled tea bowl (pottery)

by 15th generation master

geppaku yūnagashi chawan

tea bowl with pale blue drip glaze (pottery)

by 16th generation master

kahin seiki hōbin

handleless teapot (porcelain)

Keeping the potter’s wheel spinning

The Asahi-yaki kiln has single-handedly carried the flag for Japanese pottery in the Uji area for four centuries. Japan has a strong custom of passing on the family business to the eldest son, but in the case of the Matsubayashi family, Yūsuke was never put under any pressure to succeed his father. After graduating from university with a degree in political science, Yūsuke found work at a major transport company. “I wanted to get a transfer overseas,” he reflects. “But when I found out that that could be four or five years down the road from that point, taking up the family trade became a real option for me.” Based on the understanding that Yūsuke would one day take over as the 16th-generation master, younger brother Toshiyuki took himself to Tokyo, where he worked as a glass artisan after graduating from art school. Both of them note that it was only after getting out into the working world that they truly appreciated the blessing of being born into such a tremendously unique family trade.

Once he had chosen on his own terms to take over the mantle of kiln master, Yūsuke soon returned to Uji. Once he was back, he was fortunate to be able to spend a meaningful six months under the tutelage of his grandfather, the 14th head of the Asahi-yaki kiln. Later, ten years after he had started his apprenticeship, his father, passed away after a battle with cancer in the autumn of 2015. “We were all clinging to some kind of hope for his recovery, but he refused treatment and worked in the kiln until the very end, as if he knew it was his time.” The last time the kiln was fired up was a month before his passing. In the eyes of the sons watching him tend carefully to the kiln for perhaps the last time, their father looked no different to hundreds of times previous. “Every single time he fired the kiln, he gave it his absolute all. I learnt so very much just being witness to that.”

However, the history of Asahi-yaki has not been four hundred years of smooth sailing. Perhaps the biggest adjustment the pottery had to make was when the capital of Japan was moved from Kyoto to Edo, now known as Tokyo. At the time, the name Uji-cha referred to the high quality matcha indispensible to the tea ceremony. Uji-cha was prized by the shōguns of the time, who had it sent all the way to Edo in special tea canisters. As a result of this patronage, Uji experience a surge in culture, but this popularity was to wane. “Our fifth, sixth and seventh-generation kiln masters had a rough time. There are records that they had to resort to baking roof tiles and working as river porters to make a living.” Then, after years of hardship, Japanese tea culture enjoyed a revival. This was due to the beginning of sencha cultivation.

Brought to Japan from the Chinese continent, sencha has long been absorbed into Japanese culture and is now one of the cornerstones of its tea. To produce matcha, tea leaves are ground into a fine powder in a pestle. Sencha and gyokuro tea on the other hand is made by directly infusing tea leaves in a kyūsu pot to draw out their natural richness and depth. During the era of Asahi-yaki’s eighth master Chōbei, there was a surge in need for the ‘Japanese style’ kyūsu used to infuse the shaded-field gyokuro tea produced at the time. It was an enormous undertaking to add state-of-the-art kyūsu tea pots to the kiln‘s repertoire, but in hindsight the decision to do so was a key to Asahi-yaki’s revival. “During the Meiji Revival, there was a period of turbulent change as Japan opened up to the world, and many venerable kilns were forced to close. Records show that despite this our workshop was selling as many as 3000 bowls and cups per year.” Gyokuro tea is infused slowly at low temperature, and so a handleless hōbin tea pot is used. The classic hōbin design still used today is a reminder of Asahi-yaki’s revolutionary approach to adapting to shifting trends.

In contemporary Japan however, it’s far more common to drink green tea from a plastic bottle than a pottery cup or bowl. How then, does the current generation see the future role of the potter? “Our job is to nurture the contemporary culture of tea,” says Hōsai. Toshiyuki completes the thought. “As the current master deepens the artistic side of Asahi-yaki, my role is to share his work with the wider world.” To perfectly illustrate this idea, the brothers are soon to open a new gallery and store for Asahi-yaki works. The concept of the space is ‘open-plan teahouse.’ It will be a fascinating place to experience the future delights of teaware.

The clay each generation’s master uses to create their bowls is fifty years old. The clay dug this year is a legacy waiting for its time half a century into the future. In other words, there’s one hundred-year span tangible at any point in time. But amidst all this history, Asahi-yaki maintains its humble quality. The boys’ father once noted that Asahi-yaki’s strength is in its essential modesty, the way it shuns the contrived ‘look at this’ feel of some other artforms. One feels that how the Matsubayashi brothers are able to maintain this character in contemporary society will become a criterion for traditional artisans not only in Japan, but in workshops, kilns and galleries all around the world.

Pottery experiences

One-day pottery lesson

A full-day experience using the distinctive Uji clay of Asahi-yaki. Beginners welcome.

Completed items will be shipped after firing.

English instruction available.

Reservations by phone: 0774-23-2517

● Hand-shaped bowl lesson

Fee: ¥3240 (one tea bowl-sized item)

Lesson times: 10 am~, 1:30 pm~

(lesson approx. 90 mins.)

Suitable for ages: 5+

● Electric potter’s wheel lesson

Fee: ¥3780 (one tea bowl-sized item)

Lesson times: 10 am~, 1:30 pm~

(lesson approx. 90 mins.)

Class size: 4

Suitable for ages: 6+

● Painted pottery lesson

Fee: ¥3240 (plate), ¥5400 (tea cup) ¥16200 (tea bowl)

Lesson times: 10 am~, 1:30 pm~

(lesson approx. 30 mins.)

Suitable for ages: 3+

Asahi-yaki

www.asahiyaki.com

【Address】 京都府宇治市宇治山田11番地

【Access 】 A seven-minute walk from Uji station on the Keihan line, or a 17-minute walk from Uji station on the JR Nara line

【Phone】 0774-23-2511

【Open】 10 am ~ 5 pm daily

【Closed】 Mondays (when Monday is a public holiday, the Tuesday directly following), last Tuesday of the month

【Parking】 Available