Masaya Kushino

Born in 1982 on Innoshima Island, Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture. After graduating from a fashion design course at the Kyoto Institute of Design, Kushino travelled to Italy in 2004, gaining a diploma in fashion design from the Instituto Marangoni.

Returning to Japan, he was awarded the prestigious Grand Prix in the Jila Leather Goods Awards of 2007. This success encouraged him to establish his own line of leatherware, under the name Masaya Kushino. Currently based in Kyoto, Kushino continues to incorporate a range of traditional techniques into the creations he aims at the world stage.

Masaya Kushino strives to produce artistic designs in shoes that surprise and delight. His creations have been worn by global fashion icons such as Lady Gaga, and his unique talents have been recognized around the world. We sat down with Kushino to talk about his roots, his art, and the directions in which he wants to take it.

Origins a constant inspiration

Kushino grew up on Innoshima Island, a small island off Hiroshima Prefecture in the Seto Inland Sea. However, upon reaching high school, he chose to attend a school on the mainland, commuting two hours each way by bike, ferry and bus. “I didn’t want my life to be restricted to the island- I wanted to get at least one foot off,” he recalls. His desire to expand boundaries had its beginnings at this time. But it’s not that he didn’t enjoy life on the island- he spent many an idyllic hour climbing its mountains and swimming in its clear waters.

Japanese society is said to feature a typical ‘island nation’ mentality, and relatively few people have the will, or indeed the opportunity, to stretch themselves beyond its borders. The number of those who do is slowly increasing, but still quite low. Kushino had dreamt of escaping Japan from quite a young age, and in 2004, at age 22, he travelled to Italy to study fashion. “I didn’t have any particular qualms about visiting foreign countries, nor did I have any particular reason that I absolutely had to stay in Japan,” he reflects. “I went to Colorado to visit a cousin who married an American, there were foreigners living in my neighborhood, and my great-grandfather was actually Dutch.” These were all aspects from outside of Japan that had a lasting influence on young Kushino.

Finding an identity in Kyoto

Coming to Kyoto, too, was in a way inevitable. It was his first and only choice when selecting a city in which to attend design school. “Most world travelers have a wealth of knowledge about their own cultures. If I was to travel abroad in the future, I felt I wanted to know more about my own culture as a Japanese.” Kushino chose wisely. Kyoto is perhaps the most ‘Japanese’ of cities. He has been based here for 13 years now, and it feels like home.

Kyotoites are sometimes accused of being a little rude to outsiders, but once one is accepted into the circle, they are in fact quite kind. He found this to be true. “Kyoto people do have that cold fish reputation, but I think that’s just because they are honest in the way they show themselves, and at the same time uncompromising about what they want. Once you get used to it, it’s a really comfortable place to live. I’m well looked after by quite a few locals!” he laughs.

Kushino works on a number of collaborative projects. One of these is with the owner of old Nishijin-ori silk merchants Hosō, in the pipeline and due for release this coming April. “There’s a group of us who often get together, Hosō-san included. We discuss how we can remake Kyoto and its image, and sometimes get a telling-off,” Kushino laughs.

Kushino, who spends most of his time thinking about either his artwork or Kyoto, claims his only hobby is carrying mikoshi the portable shrines used in Japanese festivals. It’s a surprise to hear this rather physical pastime is beloved by the delicate-looking Kushino. “I do it at least ten times a year. It’s a way of feeling close to the gods, and I believe it gives a kind of creative energy.

Challenges propelling him forward

Kushino’s main area of expertise is women’s shoes. He had always been keenly interested in fashion, and studied fashion design, but was frustrated with the gap between the designs in his head and the clothes he was actually able to produce.

“Once I tried on the clothes I designed, they became real things, and my imagination waned. But lady’s shoes- I don’t wear them, and I don’t need to care about things like the height of the heels. My imagination is truly unleashed.” “It’s something like sculpture. Clothes only take on their complete form once they are worn, but shoes appear basically the same whether someone is in them or not.” This is the realization that changed his way of thinking about shoes from fashion into art.

A recurring motif in much of his work are natural organisms such as animals and plants. “It’s as if I can breathe some energy into these objects and create a life form,” he explains. Asked where he finds appeal in nature, he replies “I called the collection Final Design for this reason. All of nature, human beings included, is going through a critical process of change and evolution, and current stage is simply one on the way to a final design.”

I think this process is a string of recurring miracles. And it’s one that continues. In a sense, though it’s a final design, it’s one that is always new. Something that the world created? But if that’s the case, I’m not needed. I’ll continue to challenge myself with this idea. His visions of the future that he’s shared make us eager for more of his inspired work.

Two contemporaries etching a moment in history

For this issue, we had the rare opportunity of photographing a wonderful artistic partnership- the striking art shoe of Masaya Kushino and the magnificent hanging scroll painting Setsubaiyūkeizu (Rooster with plum blossoms and snow) by the renowned 18th century painter Itō Jakuchū. The result is one side of the poster you will find in the centre pages of this paper.

We spoke with Tōryō Itō, vice-head abbot of Ryōsoku-in temple, where this hanging scroll is preserved, and shoe artist Masaya Kushino about the ideas behind the collaboration and what the future might hold for their partnership.

A unique composition

Enjoy Kyoto (EK): What was the inspiration behind this collaborative shoot?

Kushino (K): In my studies of Kyoto’s history and culture I came across Jakuchū. I was inspired by his paintings of roosters and chickens, and from this created the series Bird-witched, which is the work featured in this photo shoot. I sincerely wanted the artworks I had poured my heart and soul into to be photographed with the incredible scroll painting Setsubaiyūkeizu, which is just brimming with energy. I saw it as an interesting way of creating a link between the past and present.

Vice-abbot Itō (I): To be completely honest, when Kushino first come to me with the idea I thought there was no way it would work, and tried to convince him to try another project. Setsubaiyūkeizu is one of the most precious works of art in this temple’s possession. It’s rarely photographed at all, let alone next to the works of a young artist. I guess what convinced me to agree to the shoot was Kushino’s passion, and his mettle as an artist. “I want people 100 or 200 hundred years from now to see this, if Jakuchū himself were alive I’d want him to see it.” This is the kind of passion I saw in him that made me think the work was worthy of being shot with Jakuchū’s painting, and that it might even open up something in the future.

K : I knew that what I was asking was quite brazen. I wasn’t going to give up so easily- I was willing to try again and again until I could convince him. But I’m glad I did- through this I was able to make a wonderful connection with Vice-abbot Itō.

I : I think there’s also some happy fate in this painting being here at Ryōsoku-in. There are two theories as to how this came about. The first states that Jakuchū came to the temple to view another of the paintings in its collection, Sangyōzu by the Zen priest Josetsu, who was regarded as the godfather of suiboku ink painting in Japan. Perhaps he wanted to explore the roots of this art form. Another theory holds that he visited the temple along with Daiten Oshō, who had an association with Ryōsoku-in.

K : It really struck me when you made a bow to the painting.

I : Did I do that? (laughs) It was an unconscious thing. It’s not actually a Buddhist work, but it does express a kind of Buddhist philosophy. In the cold of winter, these roosters are scratching through the earth for food with such vigor. Also in the scene you can see some modest-looking daffodils bending under the weight of snow, and the delicate hairs on the plum branch- there’s quite a strong sense of impermanence there. Everything is alive, yet imperfectly- it’s this collection of flawed living things in constant change that is so captivating.

The beginnings of a connection

EK : How do you feel about this connection that you’ve made?

K : Previously, when Vice-abbot Itō finally agreed to the shoot, after so many attempts to convince him, he also said that this artwork would be dedicated to and housed in the temple, which is such a great honor and blessing. I remember hoping at the time that we could form some kind of lasting partnership.

I : At the time, when I asked him why he worked in women’s shoes, Kushino replied, “I enjoy imaging the person wearing them.” As someone who belongs to a temple, I think it’s important to always come back to certain questions. Why was this temple founded? What kind of culture does it try to pass on? What teachings did it try to disseminate? I thought in this case if we were to craft shoes as offerings to (temple founder) Oshō in the same humble spirit that we approach the temple’s wooden idols or sculptures, then it might be a novel way of paying tribute to the founder’s ideals.

K : For me it was a truly romantic idea, the notion that this was an artwork that might be seen by future generations. So it made me realize I had to maintain a lifestyle worthy of that honor.

I : When you’re creating something that’s going to be dedicated to the temple, it gives the artwork an extra level of importance.

K : This kind of opportunity is rare, and something that every creative person dreams of. Being here, with Vice-abbot Itō in this moment feels historic too.

I : The phrase ‘in this moment’ is especially significant. Next year marks 300 years since Jakuchū’s birth, and both of us here are the same age now Cherish the knowledge of ages, adjusting it to a new era, and doing things that can only be done now- these are all things that motivate me.

K : We also have something else in common- the desire to broaden the horizons of Japanese culture around the world. I get the feeling that Vice-abbot Itō is rather a progressive type. Would you agree with that?

I : I often get asked whether I’m more progressive or conservative. I see myself as conservative. I guess the indicator is that I’m part of a family line that has been in charge of a temple for over 650 years. I maintain the respect for that, and the ambitions our forebears held, and try to update it to a contemporary context. I suppose that might be seen as ‘progressive.’

K : I strongly believe you can only break new ground by knowing your past. I really want to treasure my roots. And in the grand scheme of history, what I’m doing right now is merely a blip. But I do want to pass something on to future generations, so I’m borrowing the strength of the past. Temples, for example, are a crystallization of this idea. I really envy Vice-abbot Itō in some ways. He has a strong sense of his background, and I think this informs his identity to a large degree.

I : I am very fortunate. And I’m pleased that through this collaboration, you were able to make a connection with Ryōsoku-in, and gain some passion, some inspiration. I’m not a creator myself, so I really look forward to being able to create things in partnership in the future.

Tōryō Itō Vice-abbot of Ryōsoku-in, sub-temple of Kennin-ji

34-year-old Ito-sensei was appointed vice-abbot of Ryōsoku-in in 2008. He offers programs to the public such as zazen combined with yoga, and the meditative practice of sutra copying. Fluent in English, he is also known for hosting warm and inviting public events such as the Tora-ichi crafts market.

両足院 Ryōsoku-in

Ryōsoku-in is a sub-temple located within the grounds of Kennin-ji, Kyoto’s oldest Zen temple. Aside from a number of national treasure artworks, it is also home to a chisenkaiyu Zen garden (with a centered around a pond) registered by Kyoto City, which is open to the public twice a year. It also hosts zazen meditation experience courses for beginners.

【Address】 京都市東山区大和大路通四条下る4丁目小松町591

【Access】 7-minute walk from Gion-Shijyo station the Keihan Dentetsu railway

【Phone】 075-561-3216 【Open】 10am – 4pm

Closed to public viewing (open only for special events)

Bird-witched

The artwork’s title, Bird-witched, comes from the blending of the words bird and bewitched. In order to express the zeal (bordering on madness) for realism with which Itō Jakuchū created his work, Kushino specially ordered material from long-standing Nishijin-ori silk merchants Hosō. The hen-feather motif meticulously recreates Jakuchū’s art, down to its three-dimensionality, depth of color, and brilliant luster. The standout point, the hen’s-foot heels were specially crafted for each shoe by sculptor Takashi Nakamura, and look real enough to start scratching and moving on their own accord. The feathers that swathe the shoe were dyed to produce richer hues, and show different colors depending on angles and light. The three pieces of the work depict the gradual transformation of bird into shoe, and beautifully capture the life and energy of Jakuchū’s birds in the radically different form of footwear.

Masaya Kushino Collection

Creative Team:

■ Master shoe craftspeople: Ryuji Sado, Maki Fukuda(Perlero)

■ Sculptor: Takashi Nakamura

■ Production Director: Shunji Morino

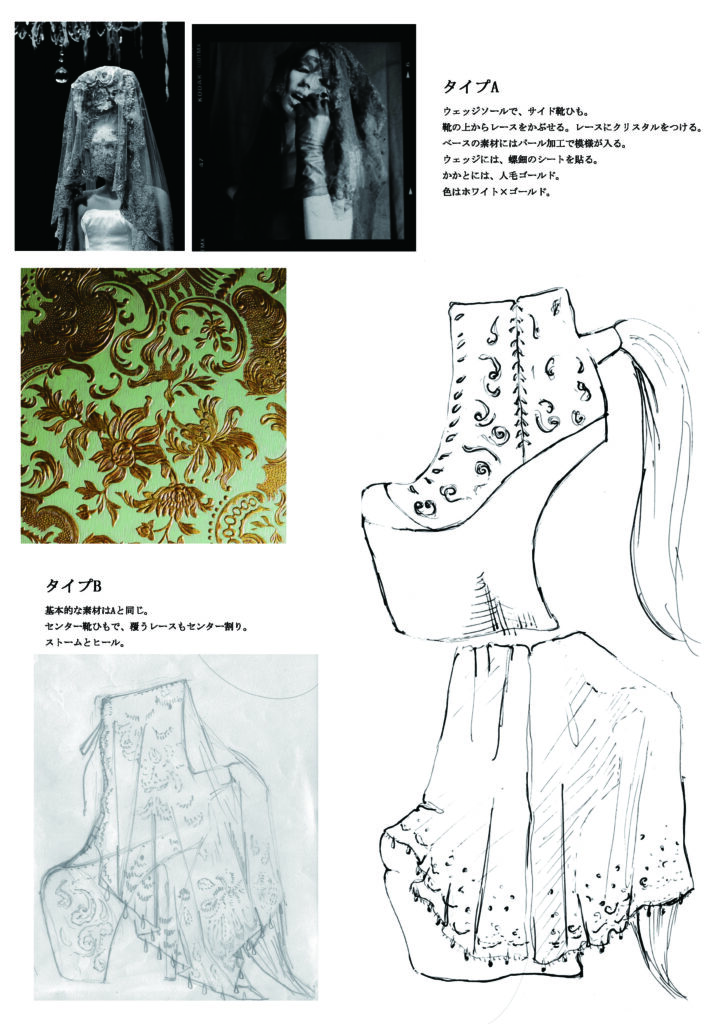

Kushino created the Three Queens series based on the question…..

If the queens in fairy tales really existed, what kind of shoes would they wear?

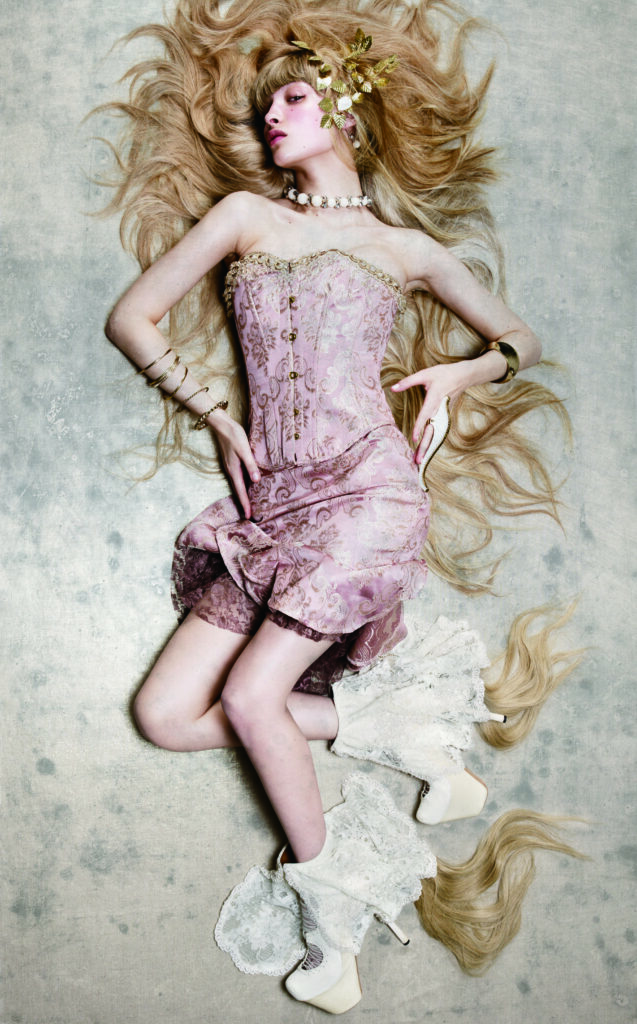

Queen of Shine

From within the delicate lace made from paper streams locks of gorgeous blond hair. The shoes are made with the skin of white stingray, which reflects the light like glittering jewels.

Queen of War

Dedicated to Jean D’Arc, this equisite pair radiates power and grace through its use of armor-like crocodile skin and deep crimson fox fur.

Queen of the Earth

Created for an imagined ‘Queen of the Earth’, the uppers of this shoe were crafted in stingray leather- which is known as ‘stone leather’ for its rigidity-embellished with crystals in progressively darker shades. The underside features polished stones, giving this creation three types of stone- natural, animal, and artificial.