Forest guide Yutaka Miura

Born in 1977 in Kyoto, Miura returned to Kyoto to become a gardener after studying architecture at Tokyo’s Nihon University. Forced to give up his dream as the result of an injury sustained during his apprenticeship, he maintained a strong interest in gardening. Convinced of the connection between natural forest and city garden, Miura spent five years journeying to woods and forests throughout Japan in search of an answer to the question, What is my definition of a good garden? After sojourning to over two thousand forests and woodlands all over the country, in 2009 Miura brought his travels to an end and returned to Kyoto. The following year he began his current job as a forest tour guide. Miura currently lives with his wife in suburb of Jōyō to the south of Kyoto.

森

mori

【forest】

Soft personality, hard working

What kind of person comes to mind when you hear the title forest guide? Perhaps you imagine a treasure hunter, a kind of Indiana Jones traveling the forests and jungles of the world in search of rare plants? Or maybe an expert in botany, a researcher at a university or pharmaceutical company, with his white coat, a mop of unruly hair, and a magnifying glass in hand collecting plant samples. Perhaps you imagine a professional gardener?

Yutaka Miura, forest guide from Kyoto, is none of those. He is quietly spoken and mild-mannered. His appearance is unremarkable, just another young man you’d pass in the street. It was out of a simple desire to teach people the pleasure of the forest that Miura chose a profession that enabled him to introduce people to his one great love, and the title forest guide.

But is it even a real profession? Turns out that’s a silly question, as Miura’s activities prove. In the six years since Miura began guided walks, his tours have continued to attract increasing numbers of participants, as do his public lectures, where he shares his considerable knowledge of the forest and its charms. His Facebook page has over 43,000 likes, and Miura also actively writes for websites and publications, as well as creating information for his own paid membership website.

Miura says, “My tours aren’t about learning more names of trees and plants, or about learning the history of the land. Of course, that kind of knowledge does make the experience more enjoyable, but first and foremost, it’s about simply walking in the forest, and being able to enjoy that time. That’s what should be the most important thing.”

You sense immediately that he’s not doing this for the fame as a researcher or for his own satisfaction. Miura genuinely wants to share his love and appreciation of the forest with others. As pure as a headwater stream flowing from deep in the forest, this honest, simple sentiment is perhaps what attracts so many to his tours.

What makes a forest?

How do we define a forest? Miura defines it simply as “Trees growing densely in a natural state.” The Japanese word for forest is mori, which derives from moriagaru meaning “to rise up”. Two thirds of Japan’s landmass was originally covered in forest. From eons ago, wherever there was soil, there grew moss, followed by grass and eventually a dense growth of numerous species of trees, which caused the ground to rise up naturally. This is the birth of a forest. On the other hand, there are the smaller scale woods, called hayashi in Japanese. This word comes from hayasu meaning “to plant”. In Japanese, there’s a clear distinction between forests, which are concentrations of trees growing naturally, and woods, which are artificially cultivated. In English one feels it’s more a question of scale.

So, how did Japan come to be blessed with such rich forests? It’s actually because the Japanese archipelago is where several different climate systems overlap. As a result, plants from different areas- continental, marine, southern, and northern- all converge over these islands. In addition, while the thick sheets of ice that covered the American and European continents during the Ice Age thoroughly stripped the land of almost all seeds, the Japanese archipelago was spared of this ice, and as a result many of the ancient species of plants that extinct in Europe and America survived here. “Compared to most developed countries, Japan probably has three to four times the species of plants,” say Miura.

Miura relates an anecdote of the moment he became acutely aware of the power of the forest. It was during his days as a architecture student at university, long before he had any real interest in gardening or forests. Walking along the street in Tokyo, Miura spotted a weed growing through the cracks in the footpath. In a defiant show of nature’s strength, the weed was breaking through the concrete that fills every last nook and cranny of this sprawling metropolis, trying to reclaim the land. Miura began to notice that in the gardens of unoccupied houses or in long-unused car parks, in fact anywhere there was a neglected man-made object or space, clumps of greenery were fighting their way through. To Miura, these growths were tiny, baby forests born right in the middle of the city. Funnily enough, my first encounter with forests was in that concrete jungle, Tokyo.”

In the five years since Great East Japan Earthquake, entry into the areas of Fukushima most contaminated with radiation has been forbidden. Gardens and asphalt in that region are overgrown with vegetation, now classified as wastelands covered by the freely growing weeds. But it is only from a human perspective that we call these places “wastelands”. From nature’s point of view, the land is reverting to forest, its most natural state. How ironic that as a result of an accident caused by a nuclear power plant, the pinnacle of human technology, a corner of Japan is once again becoming a forest, ruled by trees, plants and wild animals.

A future guided by nature

Miura had no interest in forests at all until he was 25 years old. Once he had set his sights on becoming a gardener, it was through the stylised greenery of Japanese gardens that he began to feel the allure of the forest. With his newfound interest in woodlands, Miura began to see Kyoto in an even more wonderful light than before. Traditionally, wood and forestry have played an integral part in Japanese culture. Forests and the wooden products crafted from them feature prominently in many aspects of the nation’s nature, history and religion. Timber is prominent not only in obvious examples like architecture and landscaping, but in expressions of traditional culture such as calligraphy and tea ceremony, as well as tableware and other articles of daily use. Kyoto is truly a treasury of wood and forest culture.

“When I say I work as a forest guide, people often assume I’m some kind of environmental activist. But to be honest I don’t know much about ecology or environmental issues, or organic and spiritual matters for that matter. I really just love forests and being part of them,” Miura admits. His desire to reclaim the forests as areas is fueled purely by the comfort they bring him. His simple passion is as fresh and clean like the forest air.

“These days we’ve lost a sense of the ‘fuzzy’ strength of nature. Everything must be answered with a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’, and we’re too concerned with social justice and morals. I don’t feel any color in that kind of society, nor any real groove. It’s such a pity.” Religious and racial differenes, rich and poor, employers and the employed, society and the individual. We talk about things as if they were polar opposites. But the minute you set foot in the forest, these polarizations become meaningless. This is because the blessings of the forest are immeasurably rich, and no matter what an individual is looking for, the forest will provide that person with their own kind of joy.

“In the forest, all people seem like good people, and everyone are fun to be with.” That, Miura believes, is the power of these natural havens. “My friends and I talk about buying our own forest one day and living there together. And it will be an open place where people can come and spend time there as they please.” Until then, Miura will continue to guide people to the forest, as he himself continues to be led by its transcendent power.

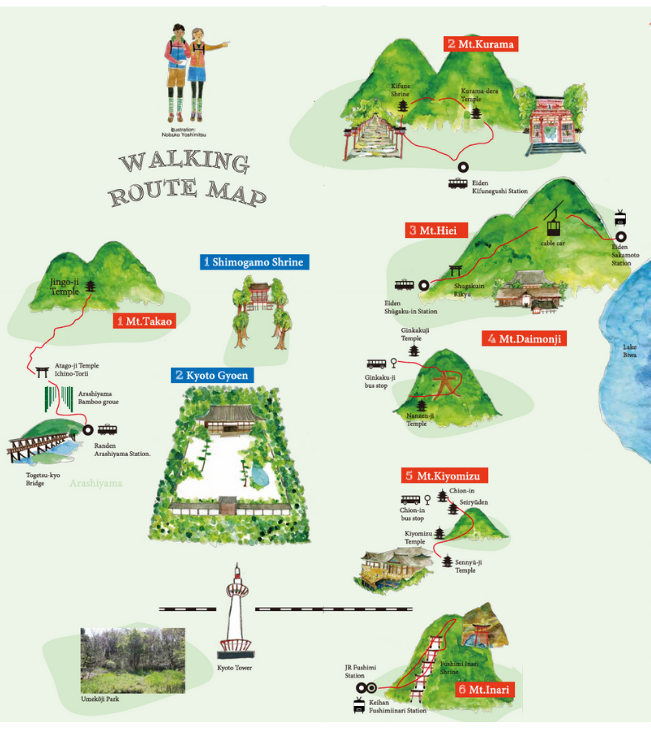

Visiting Kyoto’s Forests

“One of the interesting things about Kyoto is that there are beautiful areas of forest in and around the city,” Miura says. We asked him to introduce us to some forest walking routes he has experienced that are easily reached from Kyoto City. Japanese religions, both Shinto and Buddhism, have a deep connection with mountains and forests. Leave the hustle and bustle of the city behind as you walk along a path through the trees into the forest, and make your way up to a mountaintop shrine or a temple. You too may experience the sacred feelings and reverence for the forest that have been a part of the Japanese people since ancient times.

Inner-city forests

1⃣ Tadasu no Mori in the grounds of Shimogamo Shrine

Miura begins to talk about his favorite forest in Kyoto: Tadasu no Mori in the grounds of Shimogamo Shrine. Miura was born and raised near the Shrine, and so this sacred grove, which was in a sense his childhood backyard, is one of the most familiar forests to him. In fact, Miura’s former playground holds a secret.

Tadasu no Mori boasts a rare virgin forest, untouched since as far back as the third century BC. Miura believes that this is the only existing example of such an ancient forest surviving in the center of a city of over one million people. As part of Shimogamo Shrine, the forest is included in the Shrine’s UNESCO World Heritage listing. What is especially remarkable is that Tadasu no Mori is listed as a World Cultural Heritage Site. “In Japan forests that are heritage listed, such as Shirakami-Sanchi and Yakushima, are almost all listed as natural heritage sites. Tadasu no Mori at Shimogamo Shrine is listed as an example of cultural heritage. This is a very rare case of a forest being recognized as culture.”

When Miura was a child, nobody told him just how precious and rare Tadasu no Mori was. Perhaps one of his motivations for becoming a forest guide was to pass on the knowledge that he himself wanted. One of his earliest childhood memories planted the seed for his future calling. One thing for sure is that Tadasu no Mori holds a special place in Miura’s heart.

2⃣ Kyoto Gyoen

Another of Miura’s recommendations is Kyoto Gyoen. Managed by the Imperial Household Ministry, this central area was the location of 200 court noble residences for over one thousand years. When the capital was relocated to Tokyo around 1860, the court nobles followed suit, and the area fell into ruin. Eventually a public park was eventually established, which is said to be the origin of Kyoto Gyoen. With over 500 species of plants, the number of trees growing in the expansive Kyoto Gyoen is in the range of fifty to sixty thousand. Miura explains that the trees in the park date from three distinct eras.

The first is the trees that have been there since the days of the court noble residences, while the second comprises those donated and planted by locals when the park was developed in the late 1800s. The third type is those that grow here naturally. During the era of the court nobles, the grounds were dominated by pines and camphor trees, which were later supplemented with Japanese maples and more pines as the park was planted. Miura explains that even among the pines, there are differences between trees from different eras.

Being close to two hundred years old, the large pines from the court noble era give off a certain air of dignity. A interesting diversion as you walk through the park is to guess which era the trees are from. On the north side of the Kyoto State Guest House is an area called the “Mother and Child Forest”. When you vist, venture into the corner of this thicket where the seemingly untouched, densely growing trees are inhabited by countless insects and wild birds. It’s another world, right in the centre of our city.

Mountainside forests

1⃣ Arashiyama – Takao (approx. 8 km)

From Hankyu Arashiyama station, cross iconic Togetsu-kyō bridge and walk upstream along the Katsura River. Taking the Tōkai Nature Trail, you’ll be led through Arashiyama Park and through the famous chikurin (bamboo groves). Twenty-five minutes’ walk will bring you to the bright red torii gates of Atago Shrine. Further up the mountain road, over the steep Rokujō Pass, you’ll arrive at a winding road that follows the Kiyotaki river. Pass through the hamlet of Kiyotaki, and a good hour’s hike will bring you to the mountain village of Takao. It’s an absolutely stunning place in the autumn, especially Jingo-ji Shrine, which is the goal of this walk. The extremely fit can try to walk all the way back, but a bumpy bus ride back down the mountain is just as fun.

2⃣ Kurama – Kibune (approx. 6 km)

This route starts at Kurama station on the Eizan line, taking you through Kurama-dera temple gate, past the two-story pagoda, the main temple, Ki-no-ne michi, Maō-den (literally “Devil’s Hall”), Kifune Shrine’s innermost sanctum and main shrine, and finally to Kibuneguchi station. One caveat: descending directly from Kurama-dera Temple to Kibune was originally forbidden, as the two centers worship different gods. The correct path is come back down to Kibune-guchi after your climb to Kurama-dera Temple, before climbing up again to Kifune Shrine. There’s no need to be too particular these days, however, as the direct route from Maō-den to Kifune Shrine is the standard route.

3⃣ Shugaku-in – Hieizan – Sakamoto (approx. 10 km)

This route starts from Eizan line’s Shūgaku-in station, ascending the course along the Otowa River, past Shūgaku-in Rikyu Imperial Villa, and then up the Kirara Slope. Next, go past the cable car Hieizan station to make your way to the peak of Mt. Hiei. From there, the course descends down the mountain, taking you through Hieizan Enryakuji Temple, Konpon Chūdō (Central Hall), and Hiyoshi Taisha Shrine before arriving at Sakamoto station on the Keihan line. At over ten kilometers in length and with considerable number of hills, this challenging course requires around four hours to complete. Another option is to return to Hieizan cable car station from the peak of Mt. Hiei and ride the cable car down.

4⃣ Daimonji-yama (approx. 2 km)

Known as one of the locations of the Gozan-okuribi (“five send-off fires”) in the summer, this symbolic mountain is one of the most familiar to the people of Kyoto. Alight your bus at Ginkaku-ji bus stop, walk along Tetsugaku no Michi (Philosopher’s Walk), and head up the Ginkaku-ji road to the start of the climbing route. It takes about 30 minutes to reach the fire beds, a cleared area on the side of the mountain that is the location of flaming torches forming the character 大 (dai “big”) when the send-off fires are held. It’s a spectacular place to look back over the entire city.

5⃣ Chion-in – Kiyomizusan – Sennyu-ji Temple (approx. 7 km)

Starting at Higashiyama subway station, stop in at Shōren-in Monzeki Temple and Chion-in Temple before hiking up to Shōgunzuka Seiryū-den Temple. Hike straight down from there and head towards Kiyomizu-san, skipping Kiyomizu Temple, and instead heading from Amida-ga-mine to the Toyokuni Mausoleum. Continue from Toribeno-ryo to pay your respects at Sennyū-ji Temple. You’ll end up at Inariyama Yotsu-tsuji intersection. From there, make your way through the path of the famous Senbon Torii (thousands of torii gates) down to the main shrine for a fitting end to this busy course.

6⃣ Inariyama (approx. 6 km)

Fushimi Inari Shrine’s principal image of worship was originally located on the peak of Inariyama above the main shrine. It is said that an ancient aristocrat using mochi (pounded rice cake) placed on a branch as a target for archery practice saw the mochi transform into a bird and fly off the mountain, and then alight on the peak of the mountain. The aristocrat climbed up to the peak to find the bird had transformed again into a field of rice plants. Realising this must be a sacred place, the aristocrat built what become the shrine’s main hall. This was the origin of Fushimi Inari, one of the city’s most iconic shrines. The shrine was named Inari from the phrase ine ga naru, meaning “rice plants grow”, and the entire mountain is considered a sacred object of worship. While the myriad torii gates of Fushimi Inari are known through out the world, the story of its founding is relatively unknown. We hope you’ll see Inari in a new light and enjoy your Inariyama hike that much more.