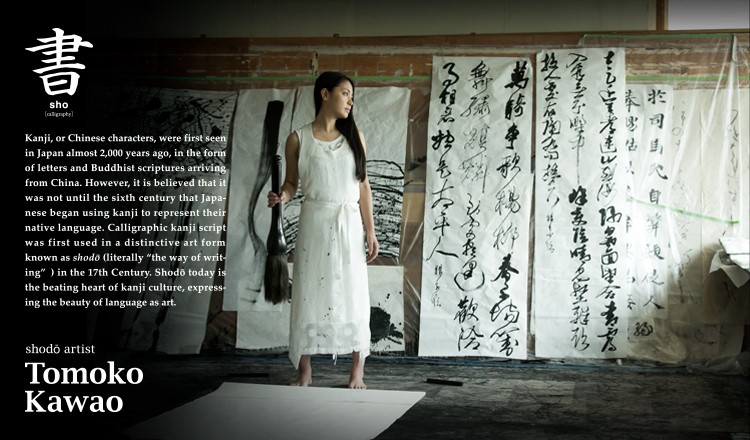

Tomoko Kawao is one of the most high-profile shodō artists in Japan today. She began her practice of the art at age six, when her parents decided to make their tomboyish daughter take shodō lessons, in the hope that this might make her more meek and feminine. Although their hopes were dashed in the sense that she never lost her knockabout personality, these lessons her parents gave her the opportunity to discover her talent and find her true purpose in life. Another factor had an enormous influence on her life and career. Kawao battled illness throughout the six years she attended junior high and high school. Up until junior high school, she had been an active and sporty child, but her inability to participate in sports caused her to often miss school, and resulted in her losing confidence and a sense of self. Though she does not like to talk about this stage of her life, Kawao refers to these years as her “dark times.”

What got her through this period was shodō. She had been familiar with the art since early childhood, and she became increasingly convinced that this was what she had to do with her life. Upon graduation from university in 2004, she rejected a job offer from a fashion company, and instead became apprenticed to shodō master Shoshu, in order to begin truly establishing herself as a shodō artist.

Advice for budding shoka

Kawao offers occasional shodō classes at temples, and has some tips for those interested in trying their hand. “Concentration is key, since writing with ink and brush is an all-or-nothing exercise. We live in a society where you can redo basically anything, but I would recommend you to keep in mind that each piece of paper gives you only one chance, and if you mess it up, that’s it. Focus is everything. For example, you can heighten your concentration through the process of grinding the ink stick. Also, just before you begin to write, take a moment to give thanks for environment that allows you to practice shodō.”

A fortunate meeting

In 2004 Kawao became acquainted with Shoshu, her mentor, through a shodō supplies store she had been frequenting for years. Seeing this master’s work for the first time, she was shocked by the reminder that her works were nowhere near the level of professional shoka (shodō artist). Her unfounded confidence, like that of many other young upstarts, was completely and quite ruthlessly shattered. She made an immediate decision to become his apprentice, convinced that he could, in her words “see something much deeper in kanji that I have yet to discover.” Every single day, Kawao continues to practice rinsho, a method of training which involves copying respected works of Japanese and Chinese shodō by sight. She still has Shoshu critique and correct her rinsho, but even after years of training, rarely receives any direct compliments from her teacher.

The essence of shodō

According to Kawao, in Japanese shodō everything begins and ends on “one layer.” This quality separates Japanese shodō from other types of calligraphy or typography and even other brush-and-ink art. She explains, “By ‘one layer,’ I mean that everything is given only one chance, and nothing is allowed to be edited or redone. This is the aspect of Japanese shodō I like best. Nothing reappears; all is transient and graceful. Each line remains uninterrupted from start to finish. Nothing can ever be done the same way once it is on paper.”

She goes on to explain the differences between Chinese calligraphy and Japanese shodō. “Chinese calligraphy is more neat and even, and feels somewhat logical. On the other hand, Japanese shodō is more free and flowing, since it contains simpler kana characters alongside kanji. Shodō treasures awahi – the white space left untouched by ink “.

Perhaps shodō is a reflection of Japanese perspectives on life and nature. Each moment passes and is gone, never to return. One tries to live life in harmony with the fleeting seasons, in oneness with the natural flow of water or clouds. During our interview, it was as if we gained some insights into our own Japanese views of life and nature, through shoka Tomoko Kawao’s own perspective on her craft.

2013 in a single kanji

During our interview with Tomoko Kawao, we asked her if she might put brush to paper and express her feelings about the past year in a single kanji. After thinking for a moment, she knelt gracefully on the floor in front of a huge white piece of paper, eyes softly closed, as if in meditation. On this particular day, a typhoon was approaching, and her studio, located right in the mountains, rattled in gusts of wind. The air was filled with tension, and an electric sense of anticipation. Something was about to happen. In the distance a bird cried out, as if trying to send us a message.

Suddenly she bowed, deeply and earnestly, and rose to her feet. Dipping an enormous brush into a well of ink, she wrote her kanji in a single breath, in one stroke. And as she wrote, we observers were also holding our breaths. The moment she finished, we exhaled with her, from deep in our stomachs. It was as if we were automatically and unconsciously responding to her breathing rhythm, sharing the same transient moment- a moment filled with both tranquility and dignity. The kanji she chose to write was 深 (fuka or shin, meaning “deep”). It is quite a common character in often used in everyday life, but also rather flexible in the sense that it can communicate different meanings depending on the usage.

For example, in Japanese you can conduct in-depth research, just as you breathe deeply, deepen a relationship, have deep feelings, and appreciate deep colours. This word can be used in a variety of ways, and yet it is also universal. What surprised us more than anything was that the kanji she chose was a perfect match for the goals of this publication – to deepen understanding and communication between foreign visitors and the city of Kyoto.

Kawao’s mission – to reinvent several thousand years of kanji tradition.

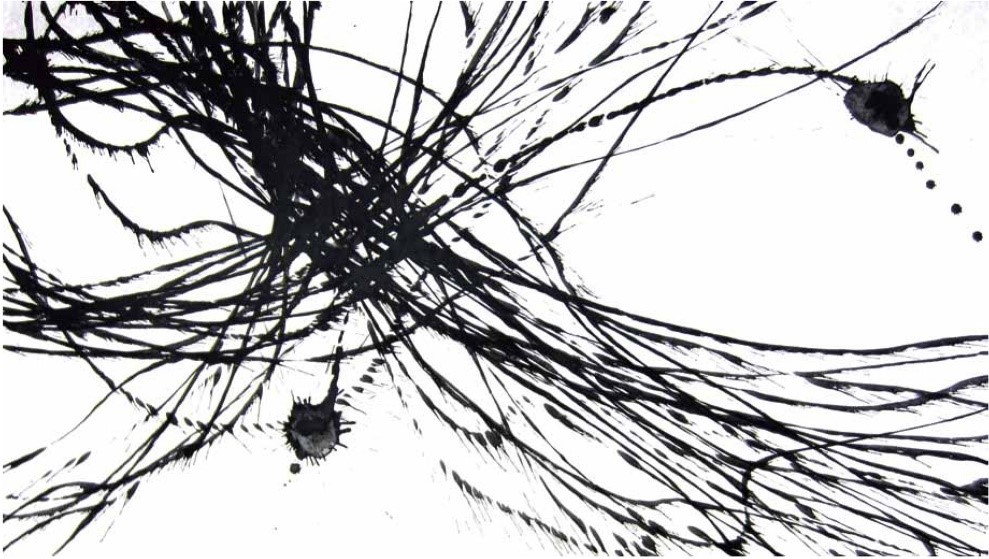

In 2009, Tomoko Kawao embarked on a career shift with a series of works entitled Correlation. At a glance, the pieces seem more like contemporary abstract paintings than calligraphy. She arrived at this point in her artistic development through ongoing rinsho training. Even now, she practices rinsho every single day. As she repeated her daily routines, copying the lines and letters of countless masterworks of eminent shodō artists, she began to pay more attention to what lay in between the lines and the flow of the letters, instead of what simply lay on the surface. Her interest piqued, she started observing small details of the writing movement, such as the arc traced by the brush between each stroke. This led her to discover the importance of picturing the movement of the brush during the process of writing. She defines this as “capturing shodō in three dimensions.”

The Correlation series was created through much trial and error. What is unique about this series is that aside from the two dark points of each work, Kawao’s brush never once comes into direct contact with the paper. In other words, the myriad lines are actually traces of ink dripping on the paper from above, as the brush moved through the air between those two points. As a result, the completed piece becomes a visual representation of the brush’s arc. The two points symbolize opposing notions, such as “you and I” or “past and future.” The sense of an invisible yet powerful “something” connecting the two points is expressed here. It is the very definition of “correlation”- the “something” that exists between a call and a response. Kawao’s unique approach to shodō has breathed fresh life into the ancient traditions of kanji. “This series is something I will continue to explore and expand upon,” she says. Perhaps we are witnessing a tradition in the making, a new precedent in the world of shodō that will continue for thousands of years hence.

【Calligraphic works】

TEDxKyoto 2013 official banner

Kawao was asked to create the official theme logo (read johakyū), for the TEDxKyoto presentations held at Kyoto University of Foreign Studies in September 2013. She was also a presenter on the day.

【Copyright 2013 TEDxKyoto】

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Kurui

Kurui, meaning ‘crazed’ is part of a new series, in which Kawao includes her own as part of the completed piece. Other works include 生 (sei/iki, the character for ‘live’).

Hankyu Arashiyama Station sign

Kawao created a shodō piece for the sign welcoming visitors as they alight from Hankyu’s Arashiyama station. Arashiyama is a popular tourist destination famous for locations such as Togetsu-kyo bridge and the Arashiyama Bamboo Forest.

Ei’un-in temple sign

A stone monument engraved with Kawao’s shodō work stands outside Ei’un-in temple, located in Kurotani-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto. Ei’un-in is a sub-temple of Konkai Komyoji, and is not usually open to the public. It is, however, used for special occasions such as art performances and film screenings.

【Performances】

Kawao often performs shodō in front of an audience- an opportunity to witness live the moment of creation. Pictured is her performance as she writes the character 心 (kokoro, ‘heart’) at a Hina-matsuri event at Seigan-ji Temple in March last year.

【Brush Art Workshops】

Kawao is active in the local community, running workshops at disabled care organization Tanpopo-no-ie, as well as shodō classes at temples.